Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level is associated with obesity and atherogenesis in adolescent boys

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

We investigated the relationship of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) level with obesity and atherosclerosis in Japanese adolescents.

Methods

We examined 492 children (247 boys and 245 girls) aged 12–13 years. The serum 25(OH)D level was compared among underweight, healthy weight, and overweight children. Spearman correlation coefficient analysis was performed to examine the relationships between the 25(OH)D level and body mass index (BMI), plasma lipids, and blood pressure and to compare the latter between the normal (≥20 ng/mL) and low (<20 ng/mL) 25(OH)D groups. Further, we performed a multiple regression analysis to assess the effect on the 25(OH)D level.

Results

The serum 25(OH)D level was significantly lower in overweight (20.5±2.7 ng/mL) than in healthy-weight boys (22.4±3.3 ng/mL) (P=0.004). Spearman correlation coefficients comparing the relationship of the 25(OH)D level with BMI, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and atherogenic index indicated significance in boys (ρ=-0.238 [P<0.0001], ρ=0.197 [P=0.002], and ρ=-0.146 [P=0.022], respectively). In boys, the multiple regression analysis results showed that BMI had negative and HDL-C had positive effects on the 25(OH)D level. The first was higher and the latter was lower in boys with low 25(OH)D level than in those with normal levels, respectively (P<0.05). No significant correlations were detected in girls.

Conclusions

Low serum 25(OH)D level was associated with obesity and increased atherogenic risk in adolescent boys only. This sex difference was probably mediated by body composition, sun exposure, estrogen, and adiponectin, which are characteristics of puberty.

Highlights

·Vitamin D deficiency is related to several health outcomes.

·Low serum 25(OH)D level is associated with obesity and increased atherogenic risk in adolescent boys but not in girls.

·This sex difference was mediated by body composition, sun exposure, estrogen, and adiponectin.

Introduction

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin that exists in 2 forms: that absorbed through the diet and that produced after the conversion of provitamin D to previtamin D in the skin upon exposure to ultraviolet rays and subsequent isomerization by body temperature. Vitamin D is metabolized sequentially in the liver and kidneys to 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, which are the major circulating and biologically active forms of vitamin D, respectively. The active form is measured as an index of abnormal calcium metabolism. Especially, 25(OH)D is the major circulating form of vitamin D and has a long half-life, because of which it serves as a nutrient index. Vitamin D plays an important role in bone metabolism, and its insufficiency causes rickets [1] and osteomalacia [2]. Recent studies have also demonstrated association between low vitamin D level and various other diseases, such as muscle weakness [3], cancers [4], autoimmune diseases [5], and type 1 diabetes [6]. Studies have also identified an association between vitamin D deficiency and major cardiovascular (CV) risk factors, such as obesity, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), diabetes mellitus, and hypertension [7,8]. The associations of vitamin D deficiency with obesity and CV risk factors have also been demonstrated in children [9]. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the association between low serum 25(OH)D level and the risk of obesity and atherosclerosis in adolescent children.

Materials and methods

In total, 492 children (247 boys and 245 girls) in the seventh grade (aged 12–13 years) were enrolled in this study. Students were recruited from 7 junior high schools located in Otawara City, Japan (36°52ʹ north latitude and 140° east longitude). Between May and July 2016, all children underwent a general health examination, which was comprised of height, weight, and blood pressure (BP) measurements. In addition, blood samples were obtained to assess the lipid levels (i.e., total cholesterol [TC], low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C], and HDL-C levels), while the 25(OH)D level from the residual serum was measured using radioimmunoassay (RIA) techniques with a DIASource 25(OH) Vitamin D total-RIA-CT Kit (DIAsource ImmunoAssays SA, Louvain-La-Neuve, Belgium). The 25(OH) D level in this population was analyzed using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test. As these levels did not follow a normal distribution (P<0.0001), a nonparametric test was warranted.

We divided the study population into the following 3 groups according to BMI percentile of the population in our cohort as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [10]: underweight (BMI<5th percentile; 10 boys and 10 girls), healthy weight (5th percentile≤BMI<85th percentile; 198 boys and 198 girls), and overweight (BMI≥85th percentile; 39 boys and 37 girls) groups. The serum 25(OH)D level was compared among these groups using a Kruskal-Wallis test. When a significant difference was found, a Bonferroni correction was applied to correct the significance probability for multiple tests.

Spearman correlation coefficients were used to evaluate the association of serum 25(OH)D level with height, weight, and BMI z-scores, as well as with plasma lipid (TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, and non-HDL-C) levels, atherogenic index (AI), and BP. The z-score used the average height, weight, and BMI of Japanese boys and girls at the relevant age based on the 2000 survey by the Ministry of Health and Welfare and previous reports [11]. We also performed a multiple regression analysis to confirm the strength of the effect on 25(OH)D level. Considering the effect of multicollinearity, the independent variable was examined and then deleted so that the Variance Inflation Factor would not be ≥10. Thus, a multiple regression analysis was performed to determine the relationships of 25(OH)D level with the BMI z-score, HDL-C, AI, and systolic BP (SBP). The study population was also divided into 2 groups based on serum 25(OH)D level: low (25(OH)D<20 ng/mL; 55 boys and 83 girls) and normal (25(OH)D ≥20 ng/mL; 192 boys and 162 girls) groups. According to the Japanese Society for Bone and Mineral Research and Japan Endocrine Society, serum 25(OH) D level<20 ng/mL is indicative of vitamin D deficiency [12]. Subsequently, height, weight, BMI, and their z-scores, AI, BP, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, and non-HDL-C levels were compared between these groups according to sex. Mann-Whitney U-tests were performed for all analyses, and P-values of <0.05 were regarded as significant.

Results

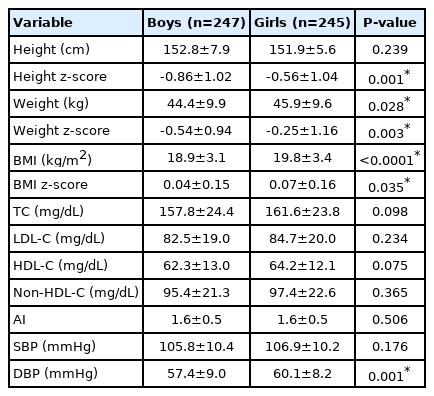

Table 1 shows the height, weight, BMI, their z-scores, plasma lipid levels, and BP of the study population according to sex. There were sex differences only in height z-score, weight, weight z-score, BMI, BMI z-score, and diastolic BP (DBP).

Table 2 shows a multiple comparison study of serum 25(OH) D level divided into 3 groups according to the BMI. The serum 25(OH)D level was significantly different among boys (underweight: 22.8±3.2 ng/mL; healthy weight: 22.4±3.3 ng/mL; and overweight, 20.5±2.7 ng/mL; P=0.005); in addition, overweight boys had significantly lower serum 25(OH)D level than healthy-weight boys (P=0.004) after Bonferroni correction. However, there were no significant differences among girls (underweight, 21.4±3.5 ng/mL; healthy weight, 21.0±3.2 ng/mL; and overweight, 20.7±2.9 ng/mL; P=0.919).

Spearman correlation coefficients comparing the serum 25(OH)D level with height, weight, and BMI z-scores and with the lipid, AI, and BP levels in 12- to 13-year-old children according to sex are presented in Table 3. In boys, correlations between serum 25(OH)D level and height z-score [ρ=-0.233 (P<0.0001)], weight z-score [ρ=-0.285 (P<0.0001)], BMI z-score [ρ=-0.238 (P<0.0001)], HDL-C [ρ=0.197 (P=0.002)], and AI [ρ=-0.146 (P=0.022)] were observed. However, no significant associations of serum 25(OH)D level were detected in girls.

Spearman correlation coefficients for 25(OH)D levels with height, weight, BMI z-score, plasma lipid levels, and BP

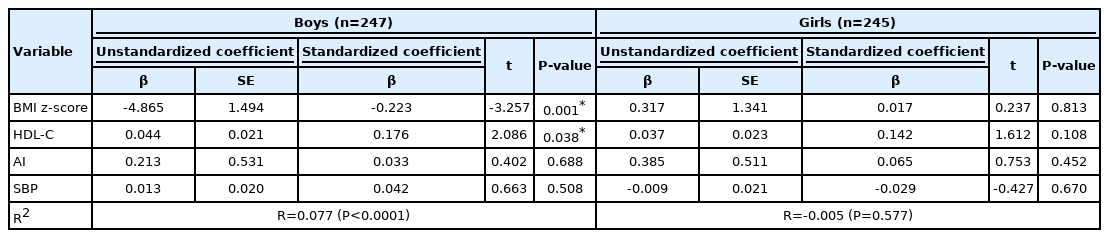

In addition, a multiple regression analysis of BMI z-score, HDL-C, AI, and SBP for 25(OH)D level showed that the adjusted R-square (R2) for boys was 0.077 (P<0.0001), while that for girls was -0.005 (P=0.577) (Table 4). The standardized coefficient β and P-values in boys were as follows: BMI z-score (β=-0.223, P=0.001), HDL-C (β=0.176, P=0.038), AI (β=0.033, P=0.688), and SBP (β=0.042, P=0.508), respectively. The BMI z-score had a negative effect on 25(OH)D level, while HDL-C had a positive effect.

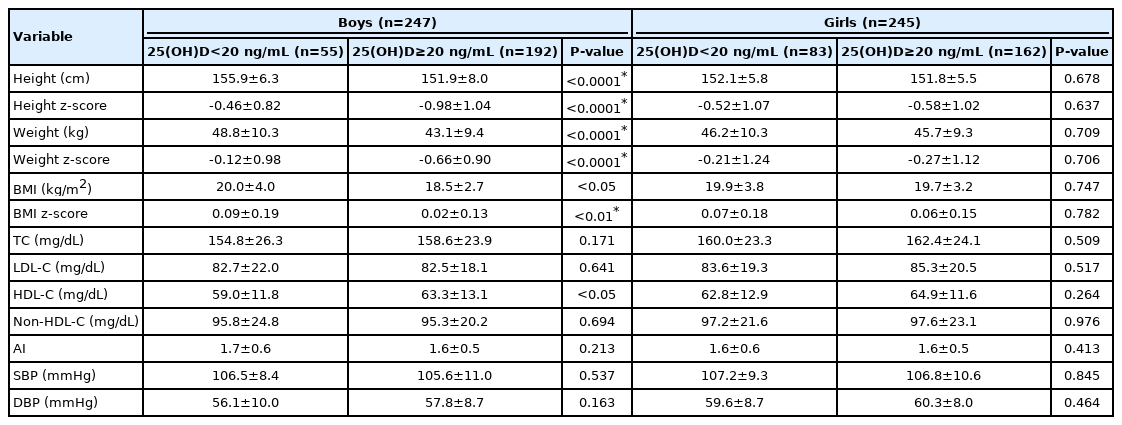

Table 5 shows the comparisons of height, weight, BMI, their z-scores, lipid levels, AI, and BP according to sex between groups stratified by serum 25(OH)D level (< 20 and ≥ 20 ng/mL). In boys, height (155.9±6.3 cm vs. 151.9±8.0 cm, P<0.0001), height z-score (-0.46±0.82 vs. -0.98±1.04, P<0.0001), weight (48.8±10.3 kg vs. 43.1±9.4 kg, P<0.0001), weight z-score (-0.12±0.98 vs. -0.66±0.90, P<0.0001), BMI (20.0±4.0 kg/m2 vs. 18.5±2.7 kg/m2, P<0.05), and BMI z-score (0.09±0.19 vs. 0.02±0.13, P<0.01) were significantly higher and HDL-C (59.0±11.8 mg/dL vs. 63.3±13.1 mg/dL, P<0.05) was significantly lower in the low compared to the normal 25(OH)D group. However, no significant correlations were detected in girls.

Discussion

Few studies have investigated the association of vitamin D deficiency with obesity and metabolic syndrome in adolescence. Therefore, we investigated the associations between serum 25(OH)D level, obesity, and atherosclerosis in Japanese adolescents. In addition, we examined the causes of sex differences.

In Table 1, which shows the anthropometry results of this population, the BMI and DBP were significantly higher in girls. According to reports on changes in body composition from adolescence to adulthood, girls aged 12–13 years tended to have higher BMI as a result of increased subcutaneous fat mass because of secondary sexual characteristics [13]. In general, BP tends to rise with obesity, and elevated DBP values have been significantly associated with increased BMI in girls [14]. The higher BMI and DBP values observed in girls than in boys in this population were consistent with those reported in previous studies [13,14].

Arunabh et al. [15] reported that obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) was associated with an increased risk of vitamin D deficiency. When vitamin D is ingested or synthesized in the skin, it is stored in fat. Therefore, it is difficult for obese individuals to biologically use vitamin D. Furthermore, when an oral dose equivalent to that of vitamin D supplementation was administered, lower serum 25(OH)D level was detected in obese compared with normal-weight individuals (BMI<25 kg/m2) [16].

Gilbert-Diamond et al. [17] reported that vitamin D-deficient children gained more weight and had greater waist circumferences than children with normal vitamin D level. Furthermore, the s er um 25(OH)D level was inversely proportional to the prevalence of metabolic syndrome, waist circumference, SBP, and homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance in children [9,18,19]. A previous study that included adult patients confirmed that the TC and LDL-C levels decreased with vitamin D intake, while the HDL-C level increased significantly [20].

In this survey, the serum 25(OH)D level was significantly lower in overweight boys than in healthy-weight boys, but there was no significant difference among girls (Table 2). Further, 25(OH)D deficiency was associated with obesity and atherosclerosis in boys but not in girls (Table 3). In addition, the BMI z-score had a negative effect, and the HDL-C had a positive effect on 25(OH)D level (Table 4).

There are 2 possible reasons for the sex difference in the association between low serum 25(OH)D level and obesity. First, in adult female patients, obesity is a risk factor for low serum 25(OH)D level [21]. Kremer et al. [22] reported that the serum 25(OH)D level was more strongly correlated with body fat percentage compared to body weight or BMI. Recently, the prevalence of normal-weight obesity syndrome has increased, especially in young women [23]. In this survey, although it was not possible to investigate the amount of body fat, it was possible that there were girls with a high body fat percentage in the healthy weight group as evaluated by the BMI. Second, the difference in the amount of sunlight exposure by sex is another possible reason. Pulungan et al. [24] reported that sun exposure duration was a major cause of vitamin D deficiency in children. Tsugawa et al. [25] reported that the serum 25(OH)D level was lower in girls than in boys during puberty, which might have been attributed to a greater amount of outdoor exercise in boys than in girls. Therefore, nonobese boys might have performed higher amounts of exercise and therefore might have received increased sun exposure than girls, regardless of body shape.

Next, another 2 issues could be related to the observed sex difference between serum 25(OH)D level and arteriosclerosis. First, estrogen (E2) secretion increases in adolescent girls, and its deficiency is associated with obesity, dyslipidemia, and arteriosclerosis [26,27]. It is also well known that E2 decreases sharply after menopause. Indeed, several studies have identified an association among E2, increases in visceral fat body, lipid metabolism, and arteriosclerosis [28,29]. The average age of puberty onset in Japanese females is approximately 10 years [30]. In addition, a survey on the national average age at menarche of Japanese girls, which was conducted in 2008, reported that 83.4% of those aged 12–13 years had reached menarche [31]. Furthermore, Villamor et al. [32] reported that vitamin D deficiency tends to lead to a premature menarche. Although we did not confirm the onset of puberty and the serum E2 level among girls in our cohort study, it can be assumed that most of the girls had already started puberty, particularly vitamin D-deficient girls who therefore might have also had high E2 levels. It is also possible that the E2 levels were higher in girls than in boys. Second, there have been some reports on the association between adiponectin and sex [33-35]. Adiponectin is one of several adipokines produced by mature adipocytes and has an antiatherosclerotic effect that repairs damaged blood vessels, promotes adhesion of macrophages to the blood vessel wall and phagocytosis of LDL-C, and acts to prevent diabetes by increasing insulin sensitivity and reducing insulin secretion [33]. Premenopausal female individuals have significantly higher adiponectin level than male individuals [34]. Plasma adiponectin level is negatively correlated with BMI in males but not in female individuals [35]. Although we did not measure adiponectin levels in this study, they might have been higher in adolescent girls than in adolescent boys, and even obese girls did not have low levels. Thus, the impact of E2 and adiponectin level might explain the lack of association between low serum 25(OH) D level and arteriosclerotic risk factors in 12- to 13-year-old adolescent girls.

Our cohort study found a negative correlation between serum 25(OH)D level and height in adolescent boys. Especially, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, the potent, biologically active form of vitamin D3, binds to the vitamin D receptor in the growth plate chondrocytes and regulates the differentiation, proliferation, and migration of osteoblasts and chondrocytes of the epiphyseal growth plate, which are cells that determine skeletal growth [36]. In addition, vitamin D has been shown to increase the levels of circulating insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and IGF-binding protein 3, with a positive correlation between vitamin D and serum IGF-I levels reported in healthy individuals [37]. Theoretically, vitamin D might have some positive effects on height.

In contrast, a research report on the effects of IGF-I and vitamin D on bone mineral density in early adolescent women stated that IGF-1 presented a positive correlation with bone mineral content (BMC), while the 25(OH)D value was negatively correlated with BMC. They further concluded that IGF-1 had a stronger influence on BMC compared to 25(OH) D [37]. In a report describing the relationship between BMC and height, children with a lower height relative to their age tended to also have a lower BMC [38].

Based on these findings, short-statured children who are prone to a low BMC might have higher vitamin D level than tall children who maintain their BMC, but the exact mechanism that varies according to sex remains unknown. Further research is needed to examine the underlying mechanisms involved in bone and molecular mechanisms that can explain the relationships between vitamin D and height and sex differences in adolescents.

This study had a few limitations. First, the blood tests were performed between spring and early summer; however, it is known that seasonality affects vitamin D level. Vitamin D deficiency is more common in the winter than in the summer months in Japan [39]. Thus, a seasonal change could have influenced the proportion of children with vitamin D deficiency. Hence, it is important to examine the results during a particular season. Second, the duration of any sunshine and sun exposure, which is required for vitamin D production, can vary widely according to the geographical location [40]. Thus, it is important to examine the results from each region. Our cohort study targeted children residing in the same area, and individual differences in sun exposure time could have influenced the outcomes. Finally, further research is needed on dietary content, outdoor activity, sex hormones (the state of menstruation for girls), and adipocytokine levels, which could not be investigated in this cohort.

In conclusion, low serum 25(OH)D level was associated with obesity and increased atherogenic risk in 12- to 13-year-old adolescent boys but not in girls. This sex difference was probably mediated by body composition, sun exposure, and E2 and adiponectin levels that are characteristic of puberty; however, this association must be clarified in future investigations.

Notes

Ethical statement

The study complied with all relevant national regulations and institutional policies and the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Dokkyo Medical University Hospital (approval number: 201606). Written informed consent was obtained from the guardians of each participant included in the study.

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan (H28-sukoyaka-ippan-006) to SK.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: SK, OA; Data curation: SK; Formal analysis: JN, SK; Methodology: SK, OA; Project administration: SK, OA; Visualization: JN, SK; Writing - original draft: JN; Writing - review & editing: JN, SK, OA, SY

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Y. Kawai for the survey support and data processing.