|

|

- Search

| Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab > Volume 27(2); 2022 > Article |

|

See commentary "Commentary on "Pathological brain lesions in girls with central precocious puberty at initial diagnosis in Southern Vietnam"" in Volume 27 on page 79.

Abstract

Purpose

Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended to identify intracranial lesions in girls with central precocious puberty (CPP). Yet, the use of routine MRI scans in girls with CPP is still debatable, as pathological findings in girls 6 years of age or older with CPP are limited. Therefore, we aimed to identify the prevalence of brain lessons in CPP patients stratified by age group (0–2, 2–6, and 6–8 years).

Methods

This retrospective cross-sectional study recruited 257 girls diagnosed with CPP for 6 years (2010–2016). MRI was used to detect brain abnormalities. Levels of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and sex hormones in blood samples were measured.

Results

Most girls had no brain lesions (82.9%, n=213), and of the minor proportion of girls with CPP that exhibited brain lesions (17.1%, n=44), 32 girls had organic CPP. Pathological findings were detected in 33.3% (2 of 6) of girls aged 0–2 years, 15.6% (5 of 32) of girls aged 2–6 years, and 3.6% (8 of 219) of girls aged 6–8 years. Hypothalamic hamartoma and tumors in the pituitary stalk were the most common pathological findings. The likelihood of brain lesions decreased with age. Girls with organic CPP were more likely to be younger (6.1±2.4 vs. 7.3±1.3 years, P<0.01) than girls with idiopathic CPP.

· Most CPP girls (82.9%) had idiopathic cause, and only 17.1% CPP girls had organic causes. Hypothalamic hamartoma and tumors in the pituitary stalk were the most common pathological findings. The likelihood of brain lesions decreased with age.

Central precocious puberty (CPP) is defined as the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics in girls before the age of 8 years and is confirmed by a positive response to the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-stimulation test [1]. In general, CPP can be classified into idiopathic CPP and organic CPP, which are both caused by central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities [2,3]. In some uncommon cases, CPP is caused by specific genetic mutations, previous excessive sex steroid exposure, and pituitary gonadotropin-secreting tumors. Children with CPP have short stature as adults, psychosocial and behavioral issues during adolescence, and high risk of hormone-related cancers in later life [4]. Therefore, GnRH agonist therapy is commonly used to prevent adverse health outcomes [4,5].

Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are recommended in girls with CPP to identify the presence of intracranial lesions that require appropriate surgical, chemotherapy, and/or radiotherapy intervention. A recent meta-analysis involving 15 studies with a total of 1,853 girls reported that brain abnormalities presented in 25% of the girls who were younger than 6 years of age and in 3% of those aged 6 to 8 years [6]. Routine cranial MRI scans are recommended for girls younger than 6 years of age because it is necessary for the early diagnosis of brain tumors and progressive pathologies of CPP. However, the prevalence of hypothalamic hamartoma in children with organic CPP aged 0–6 years was low (0.4%) [7]. Noteworthy, Yoon et al. [8] found that none of 317 South Korean girls aged 6.9±1.6 years with CPP had pathological brain lesions. Therefore, the efficacy of cranial MRI scans in girls older than 6 years of age without neurological concerns is debatable. Notably, MRI scans are potentially harmful to young children because the procedure requires sedation and the administration of contrast agents, and it also increases anxiety in children and parents. No guidelines exist for the application of MRI in the younger patient population. In addition, cranial MRI scans are expensive.

Currently, brain MRI scans are typically performed in many health centers in all girls who present with CPP and who are younger than 8 years of age to identify occult intracranial lesions. In the present study, we determined the prevalence of pathological brain lesions using cranial MRI scans to better understand the necessity of routine brain MRI scans in Vietnamese girls with CPP, especially in girls aged 6–8 years.

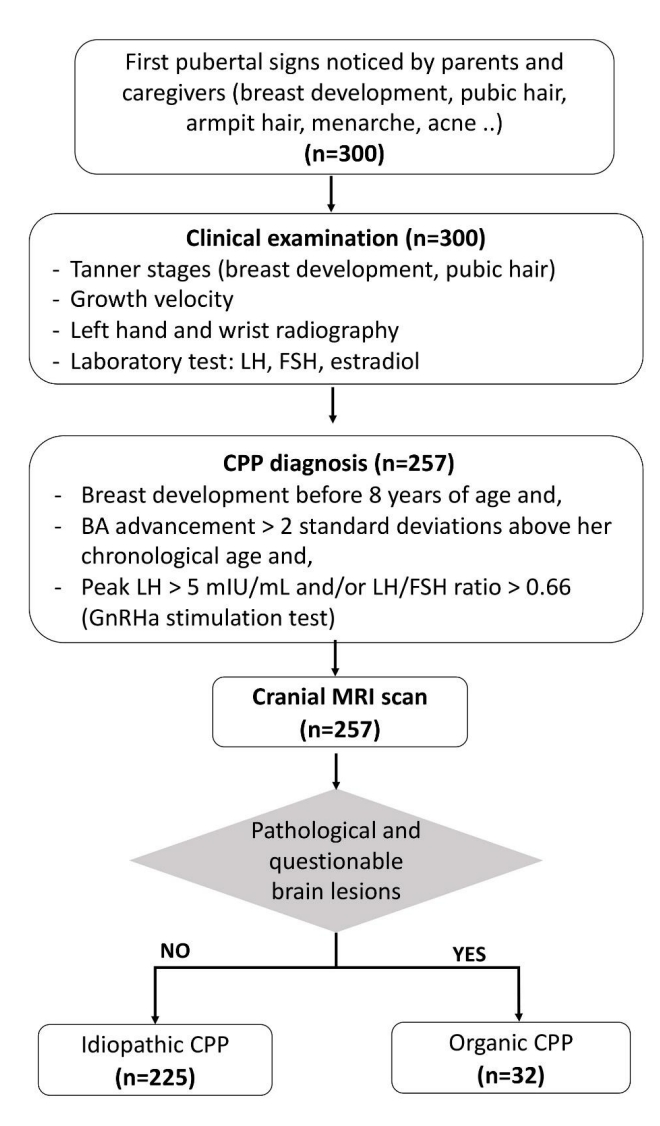

This retrospective cross-sectional study recruited 257 girls diagnosed with CPP admitted to the Children's Hospital 2, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, between January 2010 and December 2016. All selected girls underwent cranial MRI scans for study of the hypothalamus and pituitary area. Fig. 1 illustrates the study flow.

A pediatric endocrinologist examined the pubertal stage of girls according to Tanner's criteria [9]. The GnRH stimulation test has been the gold-standard test for diagnosing CPP; however, since GnRH is no longer available [10] and is of limited used in some cases, the GnRH analogue leuprolide acetate is a substitute for GnRH in the diagnosis of CPP. Hence, the GnRHa stimulation test was performed, for which a standard dose of 0.1 mg diphereline (triptorelin acetate) was subcutaneously administered. Luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels were measured at 0, 30, 60, and 120 minutes after subcutaneous injection. CPP was diagnosed in patients who developed breasts before the age of eight years and had bone age (BA) >2 standard deviations (SDs) above her chronological age (CA) and had a peak LH level ≥5 mIU/mL and/or LH/FSH ratio ≥0.66 according to the GnRHa stimulation test [3,11].

We collected data on the onset and progression of puberty (e.g., breast development, pubic hair growth, and menarche) and the detailed histories of sex steroid exposure, acquired CNS lesions, signs of a CNS lesion (such as headache, emesis, seizure, visual field defect), and puberty in parents and siblings (age at menarche) from patients and their caregivers.

We measured body weight and height to calculate body mass index (BMI) per the following formula: BMI=(body weight in kg)/(height in m)2. Height and BMI data are expressed in terms of their SD scores according to World Health Organization standards. Overweight is defined as a BMI-for-age value over +1 SD, and obesity as a BMI-for-age value over +2 SD [12].

Left hand and wrist x-rays were used to measure BA [13] mainly conducted by radiologists and pediatric endocrinologists using the Greulich and Pyle Atlas [14]. The radiologist initially determined BA, which was then reviewed by a pediatric endocrinologist. If there was a mismatch between the clinician and the radiologist, a third pediatric endocrinologist was consulted for final results. The difference between BA and CA (BA-CA) was determined as follows: BA-CA (years). Pelvic ultrasound was used to examine the condition of the uterus and ovaries. Plasma levels of basal estradiol, FSH, and LH were measured through chemiluminescence immunoassays. All children underwent cranial MRI scans to study hypothalamic or pituitary lesions using gadolinium-enhanced T1- and T2-weighted MRI (Siemens 1.5 T MAGNETOM Aera, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany).

Data are expressed as the frequency (%) and mean±SD for categorical and continuous variables. The Student t-test was used to compare the mean differences in clinical characteristics between girls with idiopathic and organic CPP. The chi-square test was used to analyze categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05. IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 25.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for descriptive and inferential statistics.

A total of 257 girls were diagnosed as having CPP and their average age at pubertal onset was 6.4±1.5 years (range, 0.83–8.0 years). The proportion of girls in the 0–2, 2–6, and 6–8 year age groups were 2.3% (n=6), 12.5% (n=32), and 85.2% (n=219), respectively. At the first visit to the clinic, the prevalence of Tanner stages 2, 3, and 4 of breast development in girls was 54.5% (n=140), 38.5% (n=99), and 7% (n=18), respectively. Girls who presented pubic hair development and menarche accounted for 30.7% (n=79) and 10.9% (n=28) of the study sample, respectively. Few patients presented with headache (organic CPP: 9.4% [3 of 32], idiopathic CPP: 1.8% [4 of 225]), and no other neurological symptoms were observed.

According to recent literature [6,7], brain insults were classified into 3 groups as determined in Table 1. In total, 44 girls with CPP (17.1%) had brain lesions, of which 34.0% (n=15), 38.6% (n=17), and 27.4% (n=12) presented pathological findings, brain lesions with questionable relationships to CPP, and incidental findings, respectively (Table 1). We grouped the girls with pathological and questionable findings (72.7%, 32 of 44) into the organic CPP group.

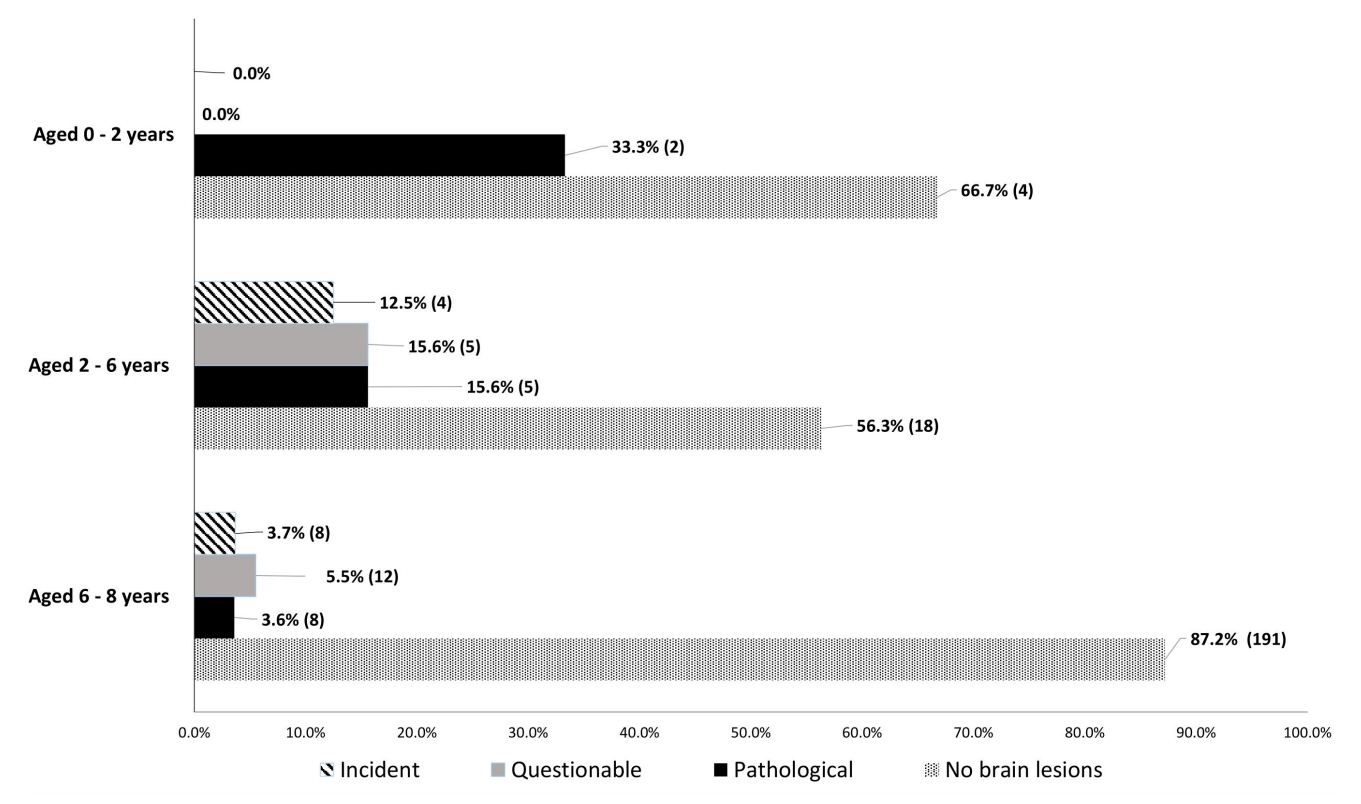

Fig. 2 illustrates the prevalence of brain abnormalities by age group. The proportion of brain lesions in girls with CPP decreased with age. Pathological findings were detected in 33.3% of girls aged 0–2 years, in 15.6% of girls aged 2–6 years, and in 3.6% of girls aged 6–8 years. At 6–8 years, girls with CPP presented a higher prevalence of questionable findings than pathological lesions (5.5% vs. 3.6%) (Fig. 2).

Hypothalamic hamartoma (20%, 3 of 15) and tumors in the pituitary stalk (20%, 3 of 15) were the most common pathological findings, followed by arachnoid cyst and small nodular lesion in the pituitary. We observed very few cases of hydrocephalus, hypothalamic tumor, germinoma in the pituitary and pineal glands, or pituitary stalk lesions (Table 1). Most patients required medical treatment; however, 5 of the 257 patients required surgical intervention, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy (3 had pituitary stalk tumors, 1 had pituitary and pineal gland germinoma, and 1 had a hypothalamic tumor).

Rathke cleft cysts (RCCs) (58.8%, 10 of 17) were the most common questionable findings concerning CPP, followed by pituitary microadenoma (41.2%, 7 of 17). Twelve girls (4.7%, 12 of 257) had incidental findings on brain MRI, such as increased pituitary volume, pituitary hypertrophy, small nodular lesions in bilateral frontal subcortical white matter, and Chiari I malformation (Table 1).

In this study, 225 (87.5%) girls had idiopathic CPP and 32 (12.5%) girls had organic CPP. Girls with organic CPP were younger than those with idiopathic CPP (6.1±2.4 years vs. 7.3±1.3 years, P<0.01). Though girls with idiopathic CPP had significantly higher body weight and height than those with organic CPP, no significant difference in BMI (standard deviation score) was observed. There was no significant difference in medical history linked to precocious puberty (PP), or in biochemical parameters between girls with idiopathic CPP and organic CPP (Table 2).

According to MRI findings in 257 girls with CPP, most girls (82.9%) had no brain lesions. In total, the prevalence of brain lesions with questionable relationships to CPP was highest at 6.6% (17 of 257), followed by pathological brain lesions (5.8%, 15 of 257) and incidental brain lesions (4.7%, 12 of 257). Pathological findings were detected in 33.3% (2 of 6) of girls aged 0–2 years, 15.6% (5 of 32) of girls aged 2–6 years, and 3.6% (8 of 219) of girls aged 6–8 years. Hypothalamic hamartoma and tumors in the infundibulum/pituitary stalk were the most common pathological findings. RCCs and pituitary microadenoma accounted for the prevalence of questionable brain lesions with CPP. In addition to clinical characteristics, the proportion of brain lesions decreased with age, and a few girls from ages 6 to 8 had organic CPP. Girls with organic CPP were younger than girls with idiopathic CPP.

In general, idiopathic CPP is the primary cause of PP in girls, and organic CPP accounts for a small fraction of the affected population. Latronico et al. [3] reported that organic CPP accounted for 8% to 33% of girls with PP. Organic CPP is defined when it is associated with a lesion of the CNS, such as hypothalamic hamartoma, suprasellar arachnoid cysts, hydrocephalus, glioma or neurofibromatosis type 1, and Chiari II malformations that were called congenital malformations [3]. The current prevalence of brain lesions in girls with CPP was lower than the pooled results of 15 studies (17.1% vs. 21.0%) [6] and a study conducted in Taiwan (17.1% vs. 21.51%) [7].

Hypothalamic hamartoma represents the leading cause of organic CPP in children before age 4 years [15]. In the current study, the average age of CPP girls with hypothalamic hamartoma was 2.1±0.7 years. Hypothalamic hamartomas induce sexual precocity by activating endogenous LH secretion via the ectopic GnRH neurons or astroglia cells transforming growth factor-α [2,16]. Patients with CPP secondary to hypothalamic hamartomas had a pubertal response to the GnRH stimulation test [17]; hence, we applied GnRH agonist therapy as the standard treatment. Regarding endocrine disorder development, hypothalamic hamartoma may cause neurological abnormalities, such as epilepsy and cognitive impairment [18].

Interestingly, we found that pituitary stalk tumor was a pathological finding in girls with CPP, which has not been previously reported in girls with CPP [6,7]. The pituitary stalk connects the hypothalamic median eminence with the pituitary gland and comprises blood vessels and nerves that help to regulate hormone function. Therefore, the reported pathological conditions such as tumor, infection, and inflammation can affect pituitary stalk function [19]. However, the clinical course of patients having pituitary stalk lesions varies from no symptoms to an increase or loss of pituitary function [20]. Kluczyński et al. [21] reported that among 60 adult patients with pituitary stalk lesions, 5 cases (8.3%) had a clinical presentation of excessive hormone production. However, no PP was observed because the recruited subjects were adults with a mean of 33.8 years. In the present study, 3 patients with pituitary stalk tumors presented normal antidiuretic hormone, adrenocorticotropic hormone, cortisol, and prolactin levels. However, the LH level increased, corresponding to the clinical diagnostic basis for CPP (data not shown).

The presence of an arachnoid cyst, hydrocephalus, and hypothalamic tumor was also reported to be associated with CPP development [6]. In our study, we had one case of the hypothalamic tumor. The exact mechanism of tumor influence on the hypothalamic-pituitary axis is not completely understood. A general concept is disruption of the normal influence of the hypothalamus on the pituitary gland [22]. One hypothesis is based on the mass effect of the tumor on the hypothalamus. In contrast, other investigators suggest the immediate release of hormones into pituitary portal circulation, affecting the pituitary gland [23]. Moreover, we reported one case of pituitary and pineal gland germinoma. Germ cell tumors were evidenced in 20% of patients with CPP because the tumor may directly impact the gonadal hormone secretion of the pituitary [24]. Intriguingly, the case of hydrocephalus was also recorded as a pathological lesion in our study. The exact pathway by which hydrocephalus disrupts the hypothalamic GnRH system is unknown; however, its theories include increased intracranial pressure, ischemia, and impairment of neurotransmitter feedback loops. Consequently, it affected the hypothalamic-pituitary axis via decreased growth hormone secretion and increased gonadotropin secretion [22,25]. Furthermore, we also classified 2 cases of arachnoid cyst as a pathological finding. Similarly, Adan et al. [26] reported that while arachnoid cysts may manifest with variable endocrine manifestations, 33% of patients with suprasellar arachnoid cysts present with CPP.

There was no clear consensus of the RCCs and pituitary microadenoma on the relationship with CPP [6,8,27,28]. RCCs are non-neoplastic sellar lesions of embryonic origin and are often clinically silent remnants throughout life [29]. However, RCCs have been linked to endocrine disorders, such as CPP, growth hormone deficiency, and idiopathic short stature [28]. Meanwhile, a previous study showed that among 34 girls having RCCs, only 46% (n=12) presented with CPP, and the treatment outcomes were similar between the CPP patients with and without RCC [30]. In the present study, most RCCs whose sizes ranged from 2–8 mm were located between the anterior and posterior pituitary glands. RCC size remained increasing in patients who underwent either surgery or non-surgery within 2 years after RCCs were detected [28]. Herein, though our CPP patients with RCCs are asymptomatic, we identified RCCs as a questionable brain disturbance to CPP. Moreover, the association of pituitary microadenoma with CPP development is under debate. Yoon et al. [8] found that 40.6% (13 of 32) of girls exhibited pituitary microadenoma, which was not considered a primary cause of organic CPP because it did not produce clinical symptoms. Meanwhile, Pedicelli et al. [31] initially classified microadenomas into the pathological brain MRI. The authors observed that girls with puberty onset at the age of 6–8 years showed the presence of pituitary microadenomas in brain MRI [31]. As stated, the follow-up MRI is recommended at 6 months and then every one to 2 years for patients with microadenomas [32]. Herein, we were convinced that pituitary microadenoma should be classified as a questionable finding to CPP development.

The proportion of brain lesions decreased with age in girls with CPP, and girls defined as having organic CPP were younger than those with idiopathic CPP. Compared with the results of the Chalumeau et al. [33] study conducted in Thailand, our results indicate a lower prevalence of brain lesions in girls aged 0–6 years (36.4% [16 of 44] vs. 72.7% [8 of 11]) and a higher prevalence of brain lesions in girls aged 6–8 years (63.6% [28 of 44] vs. 27.3% [3 of 11]). Among patients with hypothalamicpituitary lesions, the prevalence of hypothalamic hamartomas in Vietnamese girls below 6 years of age was much higher than that of Taiwanese girls (10.3% [3 of 29] vs. 0.4%) [7]. Noteworthy, Vietnamese girls exhibited fewer cases of hypothalamic hamartomas than reported in a meta-analysis study (20% [3 of 15] vs. 47.8% [68 of 142]) [6] pertaining to the pathological findings. Although MRI is recommended for the diagnosis of organic CPP [3,34], the U.S. Food and Drug Administration previously cautioned against the use of gadolinium-based contrast agents in MRI because gadolinium deposits may remain in the brain for years. Importantly, Kaplowitz [35] suggested that brain MRI should not be routinely conducted in girls with CPP aged 6–8 years because only 0%–2% of previously-unknown brain lesions required intervention in these girls. By contrast, Mogensen et al. [36] reported that 6.3% (13 of 208) of girls 6 years of age and older had pathological brain MRI findings, and 6 girls aged 8–9 years exhibited no CNS signs and symptoms. Herein, brain MRI was suggested to be frequently performed in all girls with CPP. In addition, a recent meta-analysis could not exclude the necessity of intracranial MRI for girls with CPP that are older than 6 years of age. [6] Therefore, a cranial MRI scan should be cautiously considered in girls aged 6–8 years with CPP without prior CNS signs and symptoms.

This study has several limitations. First, cranial MRI findings in girls with CPP were obtained from a single health center. Thus, we looked further at a national epidemiology study that determined the incidence of brain disturbance in the whole country. Second, this was a cross-sectional study, and we did not report on the clinical manifestations and progression of CPP caused by brain lesions.

Idiopathic CPP was more common than organic CPP in girls. Hypothalamic hamartoma and pituitary stalk tumors appeared to be the most frequent pathological brain lesion in girls with CPP. Moreover, questionable brain findings, such as RCCs and pituitary microadenoma, were noted and followed up regarding their association with CPP. Although the decreasing trend between the prevalence of brain lesions and age was observed, Vietnamese girls aged 6–8 years presented a higher prevalence of brain lesions than relevant studies. Therefore, all healthcare professionals should carefully consider cranial MRI screening for girls with CPP to avoid the potential risks of MRI, especially for girls aged 6–8 years.

Notes

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the researchers and patients at Children's Hospital 2, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, for their participation. Wallace Academic Editing edited this manuscript.

Fig. 1.

The flowchart of the study. CPP, central precocious puberty; LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GnRHa, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Fig. 2.

According to cranial magnetic resonance imaging scan, the prevalence of normal, pathological, questionable, and incidental findings in girls aged 0–2 years, 2–6 years, and 6–8 years. The P-value was derived from the Fisher exact test.

Table 1.

Characteristics of magnetic resonance imaging findings in the study population.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of precocious puberty

| Characteristic | Idiopathic CPP (n=225) | Organic CPP (n=32) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Familial early puberty, yes | 7 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 0.59† |

| Steroid hormone expose, yes | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 1.00† |

| Mother's AAM (yr) | 13.9±1.4 | 14.2±1.5 | 0.23 |

| Age (yr) | 7.3±1.3 | 6.1±2.4 | < 0.01* |

| 0–2 | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | |

| 2–6 | 22 (68.8) | 10 (31.2) | <0.01*,† |

| 6–8 | 199 (90.9) | 20 (9.1) | |

| Body weight (kg) | 30.7±6.7 | 26.2±9.3 | 0.01* |

| Body weight (SDS) | 1.5±0.9 | 1.2±1.1 | 0.26 |

| Height (cm) | 130.2±11.2 | 121.9±19.4 | 0.02* |

| Height (SDS) | 1.3±0.9 | 1.2±1.1 | 0.66 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.0±2.5 | 17.2±2.1 | 0.08 |

| BMI (SDS) | 1.1±1.1 | 0.8±1.1 | 0.28 |

| Overweight/obesity, yes | 126 (56.0) | 13 (40.1) | 0.12 |

| Tanner stage, stage 3, 4 | 99 (44.0) | 18 (56.3) | 0.64 |

| Menarche onset, yes | 21 (9.3) | 7 (21.9) | 0.06 |

| Bone age (yr) | 9.7±1.9 | 8.5±3.2 | 0.04* |

| BA-CA (yr) | 2.4±1.2 | 2.3±1.5 | 0.95 |

| Basalestradiol(pg/mL) | 32.1±21.4 | 39.1±17.4 | 0.06 |

| Basal LH (UI/L) | 1.7±2.3 | 1.9±2.1 | 0.16 |

| Basal FSH (UI/L) | 3.8±2.0 | 4.2±2.7 | 0.75 |

| Basal LH-FSH ratio | 0.4±0.6 | 0.5±0.7 | 0.49 |

| LH 30 min (UI/L) | 21.9±18.7 | 25.3±24.2 | 0.45 |

| FSH 30 min (UI/L) | 10.2±4.7 | 9.7±5.8 | 0.72 |

| LH-FSH ratio 30 min | 2.1±1.4 | 3.5±6.1 | 0.22 |

| LH 60 min (UI/L) | 24.8±24.1 | 27.3±24.0 | 0.58 |

| FSH 60 min (UI/L) | 13.2±6.5 | 12.2±6.2 | 0.41 |

| LH-FSH ratio 60 min | 1.9±1.2 | 2.2±1.7 | 0.30 |

| LH 120 min (UI/L) | 22.3±19.0 | 24.3±19.5 | 0.57 |

| FSH 120 min (UI/L) | 15.5±6.9 | 14.3±6.3 | 0.31 |

| LH-FSH ratio 120 min | 1.5±1.1 | 1.8±1.6 | 0.23 |

| Peak LH (UI/L) | 26.8±23.2 | 29.1±24.7 | 0.62 |

| Peak FSH (UI/L) | 15.7±6.1 | 14.4±6.5 | 0.33 |

| Peak LH-FSH ratio | 2.2±1.4 | 3.6±6.1 | 0.20 |

References

1. Kaplowitz PB, Oberfield SE. Reexamination of the age limit for defining when puberty is precocious in girls in the United States: implications for evaluation and treatment. Pediatrics 1999;104:936–41.

2. Jung H, Ojeda SR. Pathogenesis of precocious puberty in hypothalamic hamartoma. Horm Res 2002;57 Suppl 2:31–4.

3. Latronico AC, Brito VN, Carel JC. Causes, diagnosis, and treatment of central precocious puberty. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016;4:265–74.

4. Dossus L, Allen N, Kaaks R, Bakken K, Lund E, Tjonneland A, et al. Reproductive risk factors and endometrial cancer: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int J Cancer 2010;127:442–51.

5. Oerter Klein K. Precocious puberty: who has it? Who should be treated? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:411–4.

6. Cantas-Orsdemir S, Garb JL, Allen HF. Prevalence of cranial MRI findings in girls with central precocious puberty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2018;31:701–10.

7. Chiu CF, Wang CJ, Chen YP, Lo FS. Pathological and incidental findings in 403 Taiwanese girls with central precocious puberty at initial diagnosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020;11:256.

8. Yoon JS, So CH, Lee HS, Lim JS, Hwang JS. Prevalence of pathological brain lesions in girls with central precocious puberty: possible overestimation? J Korean Med Sci 2018;33:e329.

9. Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child 1969;44:291–303.

10. Yazdani P, Lin Y, Raman V, Haymond M. A single sample GnRHa stimulation test in the diagnosis of precocious puberty. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2012;2012:23.

11. Carel JC, Eugster EA, Rogol A, Ghizzoni L, Palmert MR. Consensus statement on the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs in children. Pediatrics 2009;123:e752. –62.

12. World Health Organization. Child growth standards [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland), World Health Organization. 2020;[cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/en/.

13. Mughal AM, Hassan N, Ahmed A. Bone age assessment methods: a critical review. Pak J Med Sci 2014;30:211.

14. Greulich WW, Pyle SI. Radiographic atlas of skeletal development of the hand and wrist. Stanford (CA): Stanford University Press. 1959.

15. Arita K, Kurisu K, Kiura Y, Iida K, Otsubo H. Hypothalamic hamartoma. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2005;45:221–31.

16. Jung H, Carmel P, Schwartz M, Witkin J, Bentele K, Westphal M, et al. Some hypothalamic hamartomas contain transforming growth factorα, a puberty-inducing growth factor, but not luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:4695–701.

17. Mahachoklertwattana P, Kaplan S, Grumbach M. The luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone-secreting hypothalamic hamartoma is a congenital malformation: natural history. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1993;77:118–24.

18. Harrison VS, Oatman O, Kerrigan JF. Hypothalamic hamartoma with epilepsy: review of endocrine comorbidity. Epilepsia 2017;58:50–9.

20. Wijetilleka S, Khan M, Mon A, Sharma D, Joseph F, Sinha A, et al. Cranial diabetes insipidus with pituitary stalk lesions. QJM 2016;109:703–8.

21. Kluczyński Ł, Gilis-Januszewska A, Godlewska M, Wójcik M, Zygmunt-Górska A, Starzyk J, et al. Diversity of pathological conditions affecting pituitary stalk. J Clin Med 2021;10:1692.

22. Brauner R, Adan L, Souberbielle J. Hypothalamic-pituitary function and growth in children with intracranial lesions. Childs Nerv Syst 1999;15:662–9.

23. Mohn A, Schoof E, Fahlbusch R, Wenzel D, Dörr H. The endocrine spectrum of arachnoid cysts in childhood. Pediatr Neurosurg 1999;31:316–21.

24. Rivarola M, Belgorosky A, Mendilaharzu H, Vidal G. Precocious puberty in children with tumours of the suprasellar and pineal areas: organic central precocious puberty. Acta Paediatr 2001;90:751–6.

25. Abdolvahabi RM, Mitchell JA, Diaz FG, McAllister JP. A brief review of the effects of chronic hydrocephalus on the gonadotropin releasing hormone system: implications for amenorrhea and precocious puberty. Neurol Res 2000;22:123–6.

26. Adan L, Bussières L, Dinand V, Zerah M, Pierre-Kahn A, Brauner R. Growth, puberty and hypothalamic-pituitary function in children with suprasellar arachnoid cyst. Eur J Pediatr 2000;159:348–55.

27. Acharya SV, Gopal RA, Menon PS, Bandgar TR, Shah NS. Precocious puberty due to Rathke cleft cyst in a child. Endocr Pract 2009;15:134–7.

28. Jung JE, Jin J, Jung MK, Kwon A, Chae HW, Kim DH, et al. Clinical manifestations of Rathke’s cleft cysts and their natural progression during 2 years in children and adolescents. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2017;22:164–9.

29. Esiri M. Russell and Rubinstein's pathology of tumors of the nervous system. Sixth edition. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;68:538. D.

30. Oh YJ, Park HK, Yang S, Song JH, Hwang IT. Clinical and radiological findings of incidental Rathke's cleft cysts in children and adolescents. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2014;19:20–6.

31. Pedicelli S, Alessio P, Scirè G, Cappa M, Cianfarani S. Routine screening by brain magnetic resonance imaging is not indicated in every girl with onset of puberty between the ages of 6 and 8 years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:4455–61.

32. Freda PU, Beckers AM, Katznelson L, Molitch ME, Montori VM, Post KD, et al. Pituitary incidentaloma: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:894–904.

33. Chalumeau M, Chemaitilly W, Trivin C, Adan L, Bréart G, Brauner R. Central precocious puberty in girls: an evidence-based diagnosis tree to predict central nervous system abnormalities. Pediatrics 2002;109:61–7.

34. Harrington J, Palmert MR, Saeger P. Definition, etiology, and evaluation of precocious puberty [Internet]. Waltham (MA), UpToDate, Inc. 2012;[cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/definitionetiology-and-evaluation-of-precocious-puberty.