Limitations of current screening methods for lipid disorders in Korean adolescents and a proposal for an effective detection method: a nationwide, cross-sectional study

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

To determine the limitations of current screening methods for lipid disorders and to suggest a new method that is effective for use in Korean adolescents.

Methods

Data from the 6th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2013–2015) were analyzed. The diagnostic validity (sensitivity and specificity) of various cardiovascular risk factors currently used for lipid disorder screening was investigated, as was the diagnostic validity of non-HDL-cholesterol ≥145 mg/dL as a screening tool.

Results

The prevalence of dyslipidemia and familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) among Korean adolescents was 20.4%±1.0% and 0.8%±0.3%, respectively. The current standard screening methods identified only 5.9%±1.4% and 30.3%±17.2% of the total number of dyslipidemia and FH cases, respectively. The diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of lipid profile analysis for dyslipidemia among obese adolescents were 19.5%±2.3% and 93.6%±0.8% and for FH were 30.3%±17.2% and 91.1%±0.8%, respectively. When adolescents with obesity, hypertension, or a family history of dyslipidemia or cardiocerebrovascular disease for over 3 generations were included in the screening, diagnostic sensitivity increased to 68.4%±2.8% for dyslipidemia and 83.5%±2.7% for FH. Universal screening of all adolescents based on non-HDL-cholesterol levels had sensitivities of 30.2%±2.7% and 100%, and specificities of 99.2%±0.3% and 94%±0.6% for dyslipidemia and FH, respectively.

Conclusions

New screening methods should be considered for early diagnosis and treatment of lipid disorders in Korean adolescents.

Introduction

Dyslipidemia, defined as abnormal serum lipoprotein cholesterol levels, is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1]. According to previous autopsy studies, fatty streaks and fibrous plaque, which are histological findings of initial atherosclerosis, can begin to appear in childhood and adolescence, and the relationship between lipid disorders and atherosclerotic lesions is well established [2-4]. Thus, it is important to diagnose and manage lipid disorders early, including during childhood and adolescence.

In 1992, the National Cholesterol Education Program of the United States and the American Academy of Pediatrics proposed total cholesterol (TC) ≥200 mg/dL and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) ≥130 mg/dL as criteria for lipid disorders, based on distributions of serum lipid levels in American children and adolescents [5]. They also recommended selective lipid screening based on lipid profile analysis considering family history of CVD or parental hypercholesteremia (TC≥240 mg/dL). Other risk factors, such as hypertension or obesity in children and adolescents for whom family history was unobtainable, were also included. In 2003, the American Heart Association proposed a triglyceride (TG) level of ≥150 mg/dL as a criterion for hypertriglyceridemia and high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) <35 mg/dL for hypo-HDL cholesterolemia [6]. Thereafter, in 2008, the American Academy of Pediatrics proposed percentiles for TC, TG, LDL-C, and HDL-C depending on sex and age, in recognition of the selective lipid screening recommended by previous guidelines [7]. However, screening for lipid disorders in childhood and adolescence based on family history of CVD or dyslipidemia has since been demonstrated to likely miss approximately 30%–60% of positive cases [7]. Based on 2011 revisions by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended universal screening using non-HDL-C levels to detect lipid disorders in all children 9–11 years old and adolescents 17–21 years old. Additionally, selective screening is performed according to risk factors and family history for children aged 2–8 years and 12–16 years. In 2011, the NHLBI reported risk factors for lipid disorders, which included a family history of CVD, such as myocardial infarction and angina, as well as smoking, hypertension, obesity, and diabetes, and these risk factors were classified into high or moderate levels [8].

TC minus HDL-C equals non-HDL-C, which reflects ApoB lipoprotein with atherogenic effects; thus, non-HDL-C and LDL-C collectively predict atherosclerosis. Since non-HDL-C is less influenced by fasting time than LDL-C, it is a useful parameter for a screening test [9-12].

However, the current screening methods for lipid disorders measure TC in obese Korean adolescents whose body mass index (BMI) is ≥95th percentile or is 25 kg/m2 among fourth graders in elementary school, first graders in middle school, and first graders in high school. In cases where TC ≥200 mg/dL, a serum lipid profile analysis (TC, TG, LDL-C, HDL-C) is usually requested [13]. Thus, a lipid profile analysis is performed after primary and secondary screenings for obesity and hypercholesteremia, respectively. This strategy could miss large numbers of adolescents with lipid disorders. This study aimed to identify the problems associated with the current screening methods and to propose a new and effective method for detecting lipid disorders among Korean adolescents.

Materials and methods

1. Subjects

We analyzed raw data from the 6th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VI), 2013–2015, managed by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Of 22,948 subjects, 2,140 who were aged 10–18 years old and who had fasted for at least 8 hours before their examination were selected, of whom 334 were excluded due to incomplete data. The final analyses were conducted on 1,806 subjects.

2. Methods

A professional survey team performed the examinations, and nurses measured blood pressure and collected blood samples. Blood pressure was measured with a cuff for children or adults using a mercury sphygmomanometer, called the Baumanometer Wall Unit 33 (W.A. Baum Co., Inc., Copiague, NY, USA). Blood samples were collected after at least 8 hours of fasting. Specimens were sent to the central laboratory on the same day and analyzed within 24 hours. Lipid profile analysis measured levels of serum TC, LDL-C, TG, and HDL-C enzymatically using kits from Pureauto SCHO-N (Sekisui Medical Co., Tokyo, Japan), Cholestest LDL (Sekisui Medical Co.), Pureauto S TG-N (Sekisui Medical Co.), and Cholestest N HDL (Sekisui Medical Co.). Analyses were performed with the Hitachi Automatic Analyzer 7600-210 (Hitachi Co., Tokyo, Japan). HDL-C levels were determined by deriving a conversion formula based on the Lipid Standardization Program from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [14]. LDL-C levels were measured using either the directly collected values when TG ≥200 mg/dL or the values calculated by the Fridewald equation (LDL-C = TC–[HDL-C + (TG/5)]) for cases with TG <200 mg/dL from 2013 to 2014. All the data for 2015 were measured directly.

3. Definitions

Based on the diagnostic criteria established by the US NHLBI, hypercholesteremia, hyper-LDL cholesterolemia, and hypo-HDL cholesterolemia were defined as TC≥200 mg/dL, LDL-C≥130 mg/dL, and HDL-C<40 mg/dL, respectively. Hypertriglyceridemia was defined as TG≥150 mg/dL based on (1) serum TG levels in the 90th percentile for Korean children and adolescents and (2) the diagnostic criteria proposed by the adult treatment panel of the US National Cholesterol Education Program [13,14]. Dyslipidemia was defined as the presence of at least one of these 4 conditions. Suspected familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) was defined as LDL-C ≥160 mg/dL without checking the family history. For convenience, "suspected FH" is described as "FH" in this study.

Obesity was defined as BMI ≥25 kg/m2 or being in the 95th percentile or higher for sex and age, based on the 2007 standard growth chart for children and adolescents. Blood pressure values were the mean values of 2 measurements, and hypertension was defined as systolic or diastolic blood pressure in the 95th percentile or higher for sex, age, and height [15]. The family history of 3 generations of brothers, sisters, parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles was investigated for physician-diagnosed dyslipidemia, ischemic heart disease, and stroke.

4. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 23.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Because the KNHANES VI data were acquired using a stratified, clustered, and systematic sampling design, we used analysis methods for complex samples, including weighted sample values. Categorical variables were presented as weighted frequencies±standard errors with percentages. The diagnostic validity (sensitivity and specificity) of various cardiovascular risk factors as screening tools for lipid disorders was calculated based on non-HDL-C levels as follows: sensitivity=true positive/(true positive+false negative), and specificity=true negative/(true negative+false positive).

Results

1. Lipid disorder prevalence

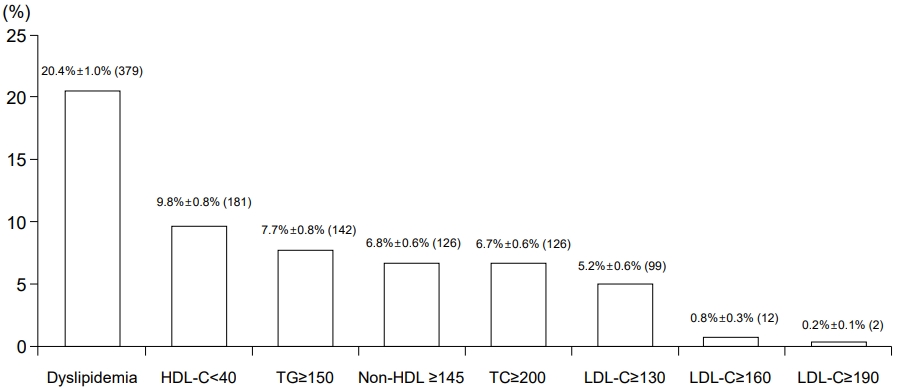

The prevalence of dyslipidemia, hypo-HDL cholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesteremia, and hyper-LDL cholesterolemia among Korean adolescents was 20.4%±1.0%, 9.8%±0.8%, 7.7%±0.8%, 6.7%±0.6%, and 5.2%±0.6%, respectively. The prevalence of LDL-C≥160 mg/dL and LDL-C≥190 mg/dL was 0.8%±0.3% and 0.2%±0.1%, respectively, and that of non-HDL-C≥145 mg/dL was 6.8%±0.6% (Fig. 1).

Prevalence of lipid disorders in Korean adolescents 10–18 years old. Data are from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey VI, 2013–2015. HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; TC, total cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol. Dyslipidemia was defined as a case with at least one of the following conditions: TC≥200 mg/dL, TG≥150 mg/dL, HDL-C<40 mg/dL, and LDL-C≥130 mg/dL. Numbers in parentheses indicate unweighted counts.

2. Identification of dyslipidemia based on current screening methods

Of the total 1,806 participants, 156 were obese, accounting for 9.1%±0.8% of cases. Twenty patients were obese and had TC≥200 mg/dL, accounting for 5.9%±1.4% of all dyslipidemia cases (379 adolescents satisfied the dyslipidemia criteria). However, 80.5%±2.3% of dyslipidemia patients were not obese, and 13.5%±1.9% of dyslipidemia patients had TC<200 mg/dL. These patients could therefore be excluded from the lipid profile analysis (Fig. 2).

Identification of dyslipidemia based on the current Korean selective screening test for lipid disorders. Boxes with dashed lines indicate likelihood to be selected at each step depending on the current screening test method for lipid disorders. Boxes with dotted lines indicate counts excluded from a screening test. Numbers in parentheses indicate unweighted counts. TC, total cholesterol.

3. Identification of suspected FH based on current screening methods

Of the total 1,806 participants, 156 were obese, accounting for 9.1%±0.8% of all suspected FH cases. Twenty patients were obese and had TC ≥200 mg/dL, accounting for 13.4%±3.0% of suspected FH cases. Of these, 3 patients were diagnosed with suspected FH (30.3%±17.2%; 12 adolescents satisfied the criteria for suspected FH). Of all the patients with suspected FH, 69.7%±17.2% were not recommended for lipid profile analysis because they were not obese, although they had TC ≥200 mg/dL (Fig. 3).

Identification of familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) based on the current Korean selective screening test for lipid disorders. Boxes with dashed lines indicate likelihood to be selected at each step depending on the current screening test method for familial hypercholesterolemia. Boxes with dotted lines indicate counts excluded from a screening test. Numbers in parentheses indicate unweighted counts. TC, total cholesterol.

4. Diagnostic validity of various cardiovascular risk factors as selection criteria for dyslipidemia screening

Table 1 summarizes the diagnostic validity (sensitivity and specificity) of various cardiovascular risk factors as selection criteria for dyslipidemia screening. A lipid profile analysis in obese adolescents yielded a sensitivity and specificity for dyslipidemia of 19.5%±2.3% and 93.6%±0.8%, respectively. Lipid analysis for adolescents whose parents had dyslipidemia yielded a sensitivity of 4.3%±1.2% (lowest value). When a lipid profile analysis was performed for patients with the largest number of risk factors, including obesity, hypertension, or family history of dyslipidemia or cardiocerebrovascular disease (ischemic heart disease and stroke) within 3 generations, the diagnostic sensitivity increased to 68.4%±2.8% (highest value).

5. Diagnostic validity of various cardiovascular risk factors as selection criteria for suspected FH screening

Table 2 summarizes the diagnostic validity (sensitivity and specificity) of various cardiovascular risk factors as selection criteria for suspected FH screening. Following a lipid profile analysis performed in obese adolescents, the sensitivity and specificity for suspected FH were 30.3%±17.2% and 91.1%±0.8%, respectively. When the same analysis was performed in adolescents whose parents had dyslipidemia, the sensitivity for FH was 5.6%±5.6% (lowest value). Higher sensitivity (83.5%±17.2%) was achieved when obesity or a family history of dyslipidemia or cardiocerebrovascular disease over 3 generations were included as criteria for selecting subjects for lipid profile analysis. Finally, the highest sensitivity (100%) was achieved using non-HDL-C≥145 mg/dL as a selection criterion.

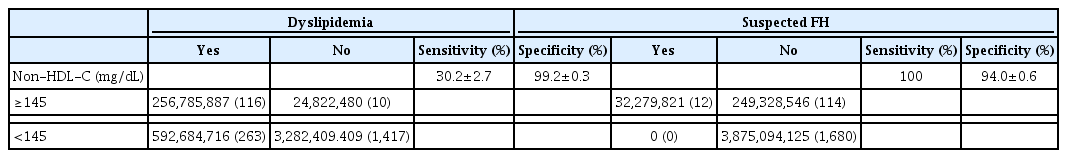

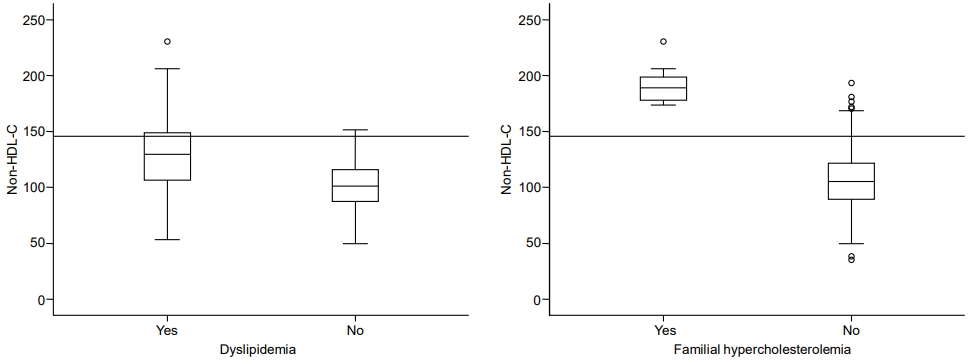

6. Diagnostic validity of non-HDL cholesterol levels as universal screening criteria for lipid disorders

Universal screening based on non-HDL-C ≥145 mg/dL yielded diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of 30.2%±2.7% and 99.2%±0.3%, respectively, for dyslipidemia (Table 2), and 100% and 94±0.6%, respectively, for suspected FH (Table 3). The distributions of non-HDL-C values for dyslipidemia and suspected FH, which were differentiated from one another based on whether the non-HDL-C was ≥145 mg/dL, are shown in the box plots in Fig. 4.

Diagnostic validity of universal screening tests based on non-HDL-C ≥145 mg/dL for lipid disorders in Korean adolescents aged 10–18 years

(A) Box plot of non-HDL-C values comparing cases with and without dyslipidemia. Median values and interquartile ranges are represented by horizontal black lines in the upper and lower bounds of the box, respectively. (B) Box plot of non-HDL-C values comparing cases with and without suspected familial hypercholesterolemia. Median values and interquartile ranges are represented by horizontal black lines in the upper and lower bounds of the box, respectively. HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol.

Discussion

In this study, we determined the validity of an existing screening method for detection of dyslipidemia and suspected FH, which are the target diseases in lipid disorder screening tests.

Our study demonstrated that the sensitivity of currently used screening tests for obese children and adolescents in Korea was as low as 5.9%±1.4%, while the incidence of dyslipidemia among the nonobese population was high (80.5%±2.3%). Several explanations for these results are possible: First, by focusing on a single high-risk group, obese patients, the screening test specificity was increased and the sensitivity was decreased, leading to an increase in the number of people with disease in the unscreened group. Second, the screening test failed to detect the correct type of patients who may need pharmacologic treatment, such as those with FH, because family history is not included in the current screening test. Consequently, in this study, we expanded the screening targets by adding children with obesity and hypertension, dyslipidemia, and whose parents has a family history of CVD/dyslipidemia over 3 generations. When the eligibility criteria for screening tests included obesity, hypertension, and a family history of dyslipidemia or cardiocerebrovascular disease over 3 generations, the diagnostic sensitivity for dyslipidemia increased to 68%±2.8% for Korean adolescents. When family history of dyslipidemia in parents alone was considered, the diagnostic sensitivity for dyslipidemia was only 4.3%±1.2%. Inclusion of 3 generations for family history of dyslipidemia increased the sensitivity to 17.6%±2.8%, which is similar to findings by Dennison et al. [16]. Sensitivity may have increased after adding additional generations to the family history because parents of young children are relatively young adults and are less likely to have developed CVD/dyslipidemia, but the probability of grandparents and great-grandparents having had CVD/dyslipidemia is higher. Therefore, to increase the identification rate of dyslipidemia through selective screening, in addition to obesity, various cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and family history of CVD/dyslipidemia over 3 generations should be considered.

However, in 2010, Ritchie et al. showed that in accordance with the National Cholesterol Education Program 1992 guidelines, when selective screening was performed only for cases where there was a family history of CVD, 36.6% of children who required pharmacologic treatment were omitted from the results. It was also argued that since the family history data were incomplete, universal screening would be helpful for early diagnosis and treatment of children and adolescents who require medication [5,17].

With regard to suspected FH, the criteria of non-HDL-C≥145 mg/dL yielded the highest sensitivity of 100%, confirming that non-HDL-C is an ideal screening marker for suspected FH.

Universal diagnostic criteria for lipid disorders have not been established. Currently, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that all children aged 9–11 years, and all adolescents aged 17–21 years, be screened for non-HDL-C [8]. Non-HDL-C is a predictive factor for CVD in adults [11,18,19]. In children, it is useful for evaluating risk of developing CVD in adulthood and it is also known to be predictive of atherosclerosis [10]. Non-HDL-C levels are more accurate than LDL-C levels when classifying CVD severity [12]. Furthermore, non-HDL-C can be a more useful criterion for screening children and adolescents because accurate values can be obtained even without fasting prior to blood sampling [20]. Shim et al. [21] have reported on the distribution of non-HDL-C among Korean children and adolescents aged 10–19 years and reported that the distribution of non-HDL-C values had a U-shaped curve according to age. The 95th percentile of non-HDL-C was 156 mg/dL in boys and 158 mg/dL in girls. These data will assist in setting appropriate cutoff points and establishing future national strategies for Korean children and adolescents.

This study analyzed the identification accuracy of current screening methods for lipid disorders using a recent large-scale national representative dataset. We also proposed an effective identification method for dyslipidemia in Korea that combines various cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, and family history of CVD/dyslipidemia. Additionally, we confirmed the diagnostic validity of the universal screening method recommended by the US NHLBI, in Korea. In other words, we confirmed the high sensitivity of universal screening for suspected FH.

The main limitation of our study is that there is no clear evidence that the screening method suggested herein will reduce CVD incidence in adults. Thus, long-term studies evaluating a causal relationship between lipid disorders in adolescence and CVD in adulthood are essential.

In conclusion, we found that universal screening with non-HDL-C was more effective for detecting suspected FH than current methods, and selective screening for a set of risk factors was a more sensitive and specific dyslipidemia detection method. Therefore, the approach currently suggested by the American Academy of Pediatrics—universal screening for certain ages (ages 9–11 and 17–21 years) and selective screening with a fasting lipid profile for children in other age groups (2–10 years old) who have risk factors—is likely appropriate. However, further research is needed to assess the adequacy of non-HDL-C cutoff values, screening frequency, and the optimal age for universal screening in Korean adolescents.

Notes

Ethical statement

All participants in the KNHANES VI provided informed consent. The protocol for the KNHANES VI was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013-07CON-03-4C, 2013-12EXP-03-5C). Additionally, this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dong-A University Hospital (DAUHIRB-EXP-18-095).

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.