Introduction

Central precocious puberty is a condition when secondary sexual characteristics are observed in girls younger than the age of eight years and in boys younger than the age of 9 years due to early activation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal axis [

1]. Increased gonadal hormonal secretion promotes bone maturation, which leads to early epiphyseal fusion and a shorter final adult height (FAH) [

2]. To prevent this, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) can be used to suppress secretion of gonadal hormones and delay early bone maturation and menarche, facilitating an increased FAH [

3].

Many studies have investigated the factors associated with FAH after treatment with GnRHa (GnRHa treatment) in central precocious puberty, which include chronological age, height, target height (TH), and predicted adult height (PAH) at the start of treatment; duration of treatment; and PAH at the end of the treatment [

4,

5]. However, very few studies to date have considered the clinical significance of birth weight relative to gestational age in children with central precocious puberty. In general, although the exact frequency differs depending on geographic region, approximately 2.3% to 10% of all newborns are born at small for gestational age (SGA)ŌĆöthat is, below the 10th percentile of birth weight corresponding to gestational age [

6]. In SGA babies, growth in the first 2 years of life is very important, and most achieve catch-up growth. However, some previous studies have suggested that 10% to 20% of SGA babies fail to achieve catch-up growth within 2 to 3 years of birth and continue to be shorter than their appropriate for gestational age (AGA) peers [

7,

8]. Moreover, SGA babies show relatively faster bone maturation and growth rates, exhibit secondary sexual characteristics earlier, and experience menarche 5 to 10 months earlier than AGA babies [

9,

10]. In contrast, other studies have reported that age at onset of puberty, pubertal growth rate, and age at menarche do not differ between SGA and AGA children [

11,

12].

Therefore, this study aimed to classify girls diagnosed with central precocious puberty according to birth weight and to compare clinical parameters such as FAH and its relationship with onset of menarche after GnRHa.

Materials and methods

1. Patients and data collection

This retrospective study identified 130 girls who were diagnosed and treated for central precocious puberty at the Department of Pediatrics at Chosun University Hospital between January 2007 and December 2017. Of these 130 girls, 69 who reached their FAH after GnRHa treatment and whose timing of menarche could be confirmed were included in the final analysis, which was conducted retrospectively based on medical records.

2. Methods

Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic central precocious puberty were (1) breast enlargement before eight years of age and (2) luteinizing hormone (LH) level (cutoff Ōēź5 IU/L) in the GnRH stimulation test. We excluded girls with brain tumor and ovarian or adrenal lesion. In addition, thyroxine and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels were measured in all patients to exclude hyperthyroidism.

Gestational age, birth weight, and height of parents were confirmed upon the initial visit in all patients. At the start of GnRHa treatment, 6 months into the treatment, and at end of the treatment, the following variables were measured: chronological age (CA), bone age (BA), height, body weight, body mass index (BMI), standard deviation scores (SDS) for height, body weight, and BMI relative to CA; peak LH/folliclestimulating hormone (FSH) ratio at the start of treatment, basal LH/FSH ratio at 6 months after treatment and at end of the treatment, TSH level, and free T4 level. FAH was measured when patients achieved a BA of 15 years or when the growth rate was less than 1 cm/yr. The time between the end of GnRHa treatment and menarche was also confirmed.

BA was measured using the Greulich-Pyle method on plain radiographs of the left hand and wrist [

13], and TH was defined as the average of parental heights minus 6.5 cm. Bayley-Pinneau (BP) average tables were used to measure PAH, and BP advanced tables were used to measure PAHa [

14].

Leuprolide acetate was administered every 28 days at a dose of 60 ╬╝g/kg in girls. To determine the SDS (standard deviation score) of physical development, the standard pediatric growth table published by the Korean Pediatric Society in 2007 was used. SGA was defined as birth weight below the 10th percentile of birth weight corresponding to gestational age; of the 69 participants, 19 were placed in the SGA group. AGA was defined as birth weight between the 10th and 90th percentiles of birth weight corresponding to gestational age; of the 69 participants, 50 were placed in the AGA group. No patient was born large for gestational age.

3. Statistical analysis

The IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 24.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Data were presented as mean┬▒standard deviation. The significance of differences between the means of clinical variables according to timing of measurement during treatment in all patients was tested through paired t-tests. The Mann-Whitney U-test, which is a nonparametric test, was used to investigate differences and significance of differences in clinical factors between AGA (n=50) and SGA (n=19) groups. In 2-sided tests, P<0.05 was set as the level of statistical significance. Simple and multiple linear regressions were used to investigate the relationship between clinical factors that may influence FAH after GnRHa treatment.

Discussion

Although previous studies have investigated puberty, growth, and FAH in SGA and AGA children, the present study remains significant as, to our knowledge [

15-

17], it is the first to investigate the effects of GnRHa treatment in SGA and AGA patients with precocious puberty. In SGA individuals, growth in the first two years of life is very important, and most babies achieve catch-up growth with normal nutrition. However, 10% to 20% of SGA babies fail to achieve catch-up growth and may experience rapid increases in body weight due to excessive nutritional intake for catch-up growth. Such rapid increases in body weight promote insulin resistance, and SGA children also have decreased insulin-like growth factor (IGF) concentration and dysfunctional IGF metabolism, which place them at an endocrinological disadvantage [

6]. Moreover, SGA children have a lower degree of insulin sensitivity relative to AGA children [

18]; it is known that high insulin concentrations stimulate LH secretion, inducing early pubertal growth [

19].

A previous study concluded that SGA children reach puberty at almost appropriate ages but experience faster pubertal growth compared with AGA children and reported that their pubertal growth rate is faster relative to their short stature [

15]. In other words, although both groups reached puberty at a similar age, the onset of puberty was earlier by 1 year on average in the SGA group than in the AGA group, and bone maturation progressed rapidly at earlier pubertal stages in the same

Similarly, in this study, BA at the time of diagnosis of central precocious puberty was significantly advanced in the SGA group at 10.9┬▒0.9 years compared with in the AGA group at 10.3┬▒0.8 years. However, during and after GnRHa treatment, the two groups had similar BA and BA/CA ratio, confirming the effects of treatment on suppression of bone maturation in the SGA group.

In another previous study analyzing onset of puberty, onset of menarche, and FAH according to birth weight in 54 girls who showed breast development between the age of eight or nine years, the groups showed similar TH profiles. However, age at the onset of menarche was significantly younger in the SGA group at 11.3┬▒0.3 years than in the AGA group at 12.9┬▒0.2 years, while the FAH was smaller by 5 cm in the SGA group relative to in the AGA group [

16]. Moreover, in 236 SGA girls and 281 AGA girls born at full term, the age at menarche did not differ significantly between 12.6┬▒1.6 years and 12.9┬▒1.7 years, respectively. Nevertheless, the FAH was significantly shorter by 3.9 cm in the SGA group than in the AGA group [

17].

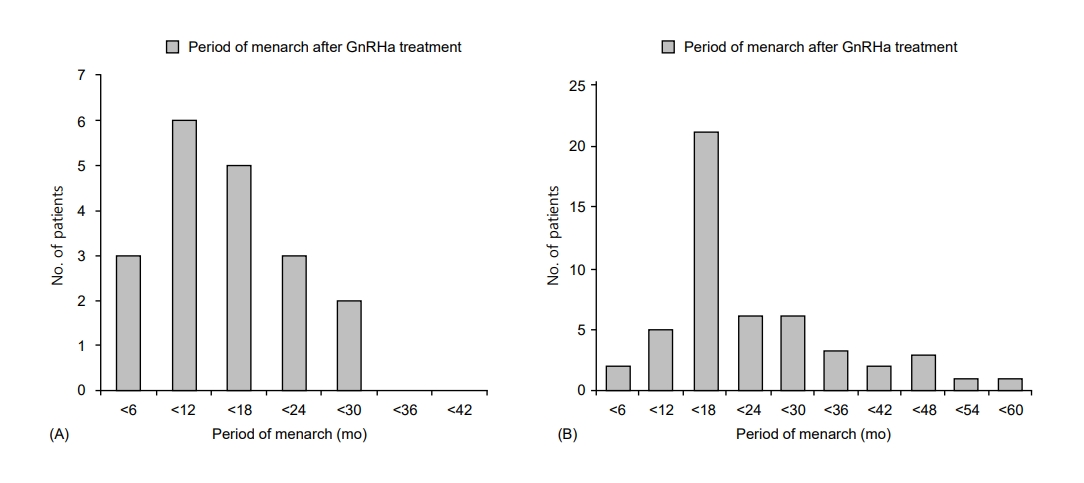

In the present study, the time between GnRHa treatment and menarche was 12.5┬▒7.6 months in the SGA group and 21.1┬▒12.3 months in the AGA group, a significant difference. These results indicate that early menarche in SGA children may be associated with early onset of puberty, which is generally observed in SGA children. However, in this study, the onset of menarche was noted after treatment for more than 30 months in 20% of the subjects in the AGA group; hence, the impact of this will need to be considered.

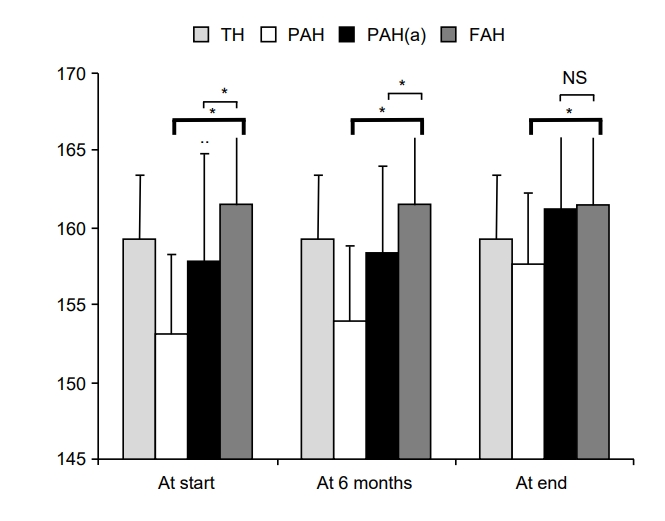

Compared with previous studies, the present investigation determined that the TH at the time of diagnosis of central precocious puberty was similar in the SGA and AGA groups; after GnRHa treatment, the FAH increased beyond the TH in both groups. In other words, the FAH was 161.0┬▒4.7 cm in the SGA group and 161.6┬▒5.0 cm in the AGA group, without any significant difference. This suggests that GnRHa is effective in increasing the FAH in both AGA and SGA children. GnRHa treatment is a standardized treatment for central precocious puberty, and the FAH is similar or improved relative to TH after treatment [

4,

5,

20]. Similarly, in this study, the PAH was smaller than the TH at the time of diagnosis of central precocious puberty in all patients, but the PAH increased during treatment and ultimately exceeded the TH at the end of treatment.

When the BP average and advanced tables are used to calculate the PAH in central precocious puberty, the prediction made based on the BP advanced table may result in overestimation of normal child growth. It is known that measuring the PAH using the BP average table is more useful in patients who have not received GnRHa treatment, and the BP advanced table produces predictions closer to the FAH in patients receiving GnRHa treatment [

21]. In addition, in this study, considering the relationships between FAH, PAH, and PAHa measured using the BP average and advanced tables, the FAH was close to the PAHa measured using the advanced table.

This study investigated the clinical significance of GnRHa treatment in girls with central precocious puberty according to birth weight. SGA patients may show early bone maturity and puberty; thus, their FAH may be lower than that in the AGA group. However, in this study, we confirmed the effects of bone maturity suppression on SGA in CPP, and that the FAH showed a greater increase than the TH.

This study has some limitations. Since this study had a small sample size, the significance of clinical variables after GnRHa treatment and FAH according to birth weight in girls with central precocious puberty should be investigated further in larger groups with longer-term follow-up. Moreover, this study used the standard pediatric growth table published by the Korean Pediatric Society in 2007, but a revised version of the table was published in 2017 that may yield slightly different outcomes. Further research can be conducted using the standard deviation in physical development presented in the new table published in 2017, and the results can subsequently be compared.