Follow-up of infants with congenital hypothyroidism and low total thyroxine/thyroid stimulating hormone on newborn screen

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Newborn screening (NBS) methods to detect congenital hypothyroidism (CH) vary regarding whether total thyroxine (T4), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), or both are measured. Neonates with low T4 and normal or low TSH (lowT4/TSH) may only be detected by T4-inclusive methods or age-dependent repeat screens. Premature neonates and those with pituitary-hypothalamic disorders frequently manifest lowT4/TSH.

Methods

This is a retrospective case-study of newborns who were screen-positive for lowT4/TSH in Alabama in 2009–2016 using a combined T4 and TSH method and 2 routine NBS. The clinical, laboratory, and final diagnosis after 3 years were determined.

Results

Over 8 years, 225 infants were referred to our institution for evaluation and treatment of CH. Twelve infants were screen-positive for lowT4/TSH by first or second NBS. Four of the 12 infants had permanent CH (30%): 2 with primary and 2 with central etiologies. One infant with moderately severe central CH was only detected by the routine second NBS. Six of 7 premature infants had elevated TSH on serum confirmation labs consistent with a delay in hypothalamic-pituitary maturation, yet 2 of these patients were later established to have permanent primary CH. While most cases of lowT4/TSH resolved by 3 years of age, several neonates had extended periods of moderate to severe hypothyroxinemia prior to detection and treatment.

Conclusions

One third of the infants with lowT4/TSH on NBS in this study had permanent CH. These results emphasize the importance of T4-based assay methods, subsequent (repeat) screens and long-term follow-up in the management of neonates with lowT4/TSH on newborn screen.

Introduction

Congenital hypothyroidism (CH) affects between 1:2,000 and 1:3,000 infants worldwide and is a common cause of preventable intellectual disability [1]. Neonates with CH are often asymptomatic and detected by newborn screening (NBS) on whole blood spot samples. Methods for NBS detection and CH diagnosis vary throughout the United States based on the number of screens (1, 2 or more) and laboratory assays performed (total thyroxine [T4], thyroid stimulating hormone [TSH], or algorithms for both). Alabama routinely measures both T4 and TSH on all specimens and furthermore obtains 2 newborn screens (at different ages) on over 95% of babies. Eleven other states also routinely employ a second NBS [2]. Several retrospective studies have examined the impact of 2 screen methods for CH using different lab methods, timing, and study populations, with the most recent reports demonstrating that approximately 20% of new CH diagnoses are detected by the second screen [3-5].

The combination of low T4 with normal to low TSH (lowT4/TSH) in neonates most commonly suggests hypothalamic/pituitary insufficiency or thyroid binding globulin (TBG) deficiency. Preterm infants have been shown to have a delayed TSH surge due to hypothalamic immaturity that may initially present as lowT4/TSH on NBS [6-8]. Of note, follow-up of preterm infants with eutopic thyroid glands has also demonstrated both permanent CH and persistent hyperthyrotropinemia in many of these neonates [8,9]. Central congenital hypothyroidism (CCH) may be detected by NBS; however, it also presents clinically following the newborn period [10,11].

As part of a large 8-year study examining the clinical outcome of 225 infants who were screen-positive for CH in Alabama by the first or second NBS, we observed 12 neonates whose results demonstrated lowT4/TSH. This report presents their clinical description and final diagnosis after 3 years. While common experience suggests that most neonates with lowT4/TSH on NBS, especially those who are preterm or critically ill, have transient thyroid dysfunction, longitudinal follow-up may uncover a range of permanent hypothyroidism. This situation is especially relevant to neonatal intensive care units (NICU), subspecialty, and primary care practitioners who are tasked with the long-term follow-up care of these babies.

Materials and methods

1. Study design

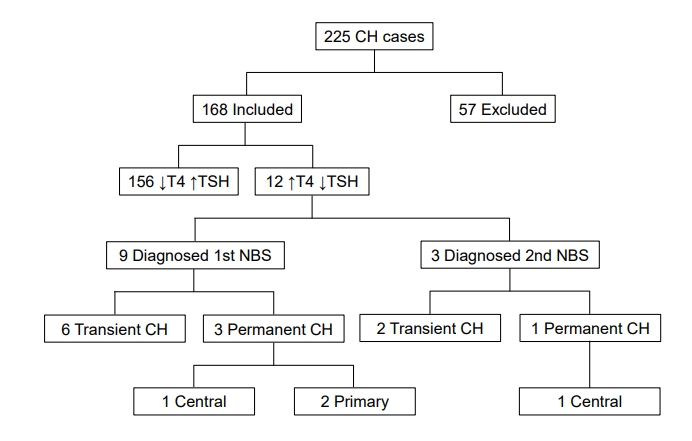

Twelve infants were identified on NBS with lowT4/TSH. The infants were extracted from a larger retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with CH in Alabama between 2009 and 2016. Approximately 472,000 infants were screened over 8 years and over 95% of screen-positive CH was referred for evaluation and care at our academic center. As shown in the Fig. 1, 225 patients with CH were identified (overall prevalence of CH 1:2100). A total of 168 patients were included for study, and 57 patients were excluded based on the study criteria, the most common being the lack of 2 NBSs for analysis.

Patients with congenital hypothyroidism (CH) detected by newborn screen (NBS) in Alabama between 2009 and 2016. T4, total thyroxine; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

Of the 57 excluded patients, 11 were screen-positive with lowT4/TSH and all had normal thyroid ultrasounds. Of these 11 excluded patients, 2 moved out of state and 1 is deceased. Of the remaining 8 patients, 5 were premature (estimated gestational age [EGA], 23–25 weeks): 3 continued 12.5–25 μg levothyroxine daily and 2 discontinued treatment with normal follow-up labs. Of the 3 term infants in the excluded group, 1 has CCH, 1 had congenital nephropathy with resolution of hypothyroidism postkidney transplant, and the third infant had TBG deficiency requiring no treatment.

2. Clinical evaluation and laboratory methods

In Alabama, the first NBS is usually obtained between 24 and 72 hours of age and the second sample between 1 and 6 weeks of age. In general, >95% of all infants undergo 2 screens. For sick or preterm infants, protocols recommend a first NBS on arrival to the NICU, a second NBS at 72 hours, and a third NBS at 2–6 weeks of age. Both total T4 and TSH are measured on all specimens using a time-resolved fluoroimmunoassay (Perkin Elmer Genetic Screening Processor). The normal range for the NBS bloodspot T4 is 76.1–322.5 nmol/dL and for TSH <25 mU/L on all screens. Concerning screen-positive infants who are otherwise well, healthcare providers follow state-wide protocols for repeat testing. For example, if the initial NBS shows low T4/normal TSH, immediate repeat bloodspot for T4/TSH is recommended. If the repeat is also positive, then serum labs are advised. Prior to treatment, positive screens were confirmed by serum free T4 and TSH using standard commercial labs. The interpretation of diagnostic serum labs depends on many factors, including chronological/gestational age, maternal history, clinical exam and other endocrine labs, medical history and thyroid imaging. We followed consensus recommendations [1] and other helpful guidelines [12,13] regarding the evaluation and treatment of CH. Specifically, for low free T4/TSH, we would reconfirm hypothyroxinemia by serial testing every 1–2 weeks and consider additional clinically-relevant testing of pituitary/hypothalamic function. Thyroid ultrasound (color Doppler) was usually done between 2–4 weeks of age or when CH was confirmed.

3. Follow-up diagnosis

The final diagnosis of the 12 patients was determined by a 3-month trial discontinuation of levothyroxine at 3 years of age if all TSH values while on treatment were <10 mU/L. Persistent hyperthyrotropinemia was defined as TSH=6–10 mU/L with normal free T4 [1,14]. The decision to restart levothyroxine in infants with TSH between 6–8 mU/L (and normal free T4) is especially contestable [15,16]. Our approach is to follow serial labs every 3–6 weeks concerning trends as well as the clinical situation (family history, thyroid imaging, growth) prior to initiating levothyroxine. If TSH >10 mU/L or free T4 was low, permanent CH was diagnosed. If any TSH value exceeded 10 mU/L while on treatment, the diagnosis of permanent primary hypothyroidism was also confirmed. In contrast, permanent CCH was defined by low free T4 without an appropriate increase in TSH with consideration of other potential pituitaryhypothalamic insufficiency.

Results

1. Patient demographics

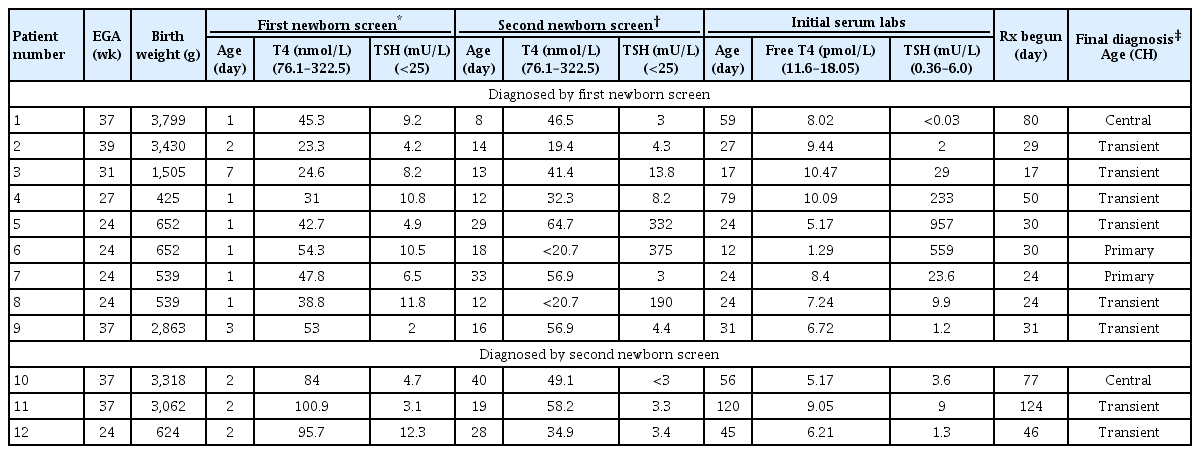

As shown in Table 1, 5 neonates were full term (gestational age≥37 weeks) while 7 were premature; the premature cases included a set of quadruplets (cases 5–8). The group included 8 males and 4 females; 11 were Caucasian and one infant was African American (case 10). None of the patients had Trisomy 21, other known chromosomal anomalies, or congenital heart disease.

2. NBS results

As shown in Table 1, 9 patients (cases 1–9) had low T4 and normal TSH on the first NBS while 3 infants (cases 10–12) had a normal first NBS and abnormal second NBS (also low T4 with normal TSH).

1) Patients detected by 1st NBS (cases 1–9)

Mean values on the first NBS were T4=40.0 ±11.5 nmol/L (mean±standard deviation) with a range of 23.3 to 54.3 nmol/L and TSH=7.56 ±3.37 mU/L with a range from 2.0 to 11.8 mU/L. The second NBS on these 9 patients revealed hypothyroidism (T4=44.1±15.5 nmol/L). However, the TSH on this group was elevated in patients 5, 6 and 8 (consistent with the delayed TSH surge of prematurity, mean TSH=298±97 mU/L) while the TSH was normal in the remainder of patients (cases 1–4, 7, and 9). Case 7 was on levothyroxine when the second NBS was obtained.

2) Patients detected by 2nd NBS (cases 10–12)

The first NBS was normal in patients 10–12. The second NBS detected a low T4 (47.7±11.6 nmol/L) in concert with a normal mean TSH of 3.2±0.2 mU/L.

3. Confirmatory serum labs

Confirmatory serum labs were obtained on day 32±15 in 11 of the 12 patients. One patient, case 11, had an unusually protracted time to serum diagnosis at 120 days. Based on the serum thyroid values, 7 patients had elevated TSH on serum lab testing (mean serum free T4=7.4 ±3.2 pmol/L (range, 1.3–10.5 pmol/L) and mean TSH=260 ±340 mU/L (range, 9–957 mU/L), while 5 patients continued to have low T4 and normal TSH (mean free T4=7.1±1.6 pmol/L and mean TSH=2.0±1.1 mU/L (range, 1.3–3.6 mU/L) (Table 1).

4. Thyroid ultrasound

The thyroid ultrasound was normal in all patients.

5. Clinical follow-up

Patients commenced thyroid hormone treatment on average by day 30 of life, except for 3 cases (1, 10, and 11) in which treatment was much later. Cases 1 and 10 had CCH and case 11 had an extended period of borderline values (Table 1). All patients were treated with levothyroxine with an average dose 27±12 μg/day for a minimum of 3 years. In the patients with possible CCH, other pituitary hormone deficiencies were excluded.

Based on the final diagnosis criteria (in methods), 2 infants (cases 6 and 7) were diagnosed with permanent primary CH and 2 infants (cases 1 and 10) had permanent CCH. Case 1 had a small Rathke cyst identified by magnetic resonance imaging while case 10 has not been imaged yet. Abbreviated case descriptions are given in Table 2.

Discussion

The purpose of NBS for CH is to detect primary hypothyroidism (low T4, high TSH) and initiate levothyroxine treatment to prevent cognitive impairment. Nevertheless, some newborns present with low T4 and normal or low TSH for various reasons, including hypothalamic-pituitary immaturity of the preterm infant, euthyroid sick syndrome, and CCH [17]. We identified 12 patients who presented with low T4 and normal TSH on either their first or second NBS. Unique to this report, we present 3-year follow-up information on the final CH diagnosis. Most noteworthy, 4 of the 12 patients (30%) were shown to have permanent hypothyroidism, including 2 term infants with CCH and 2 premature infants with primary CH. Without longitudinal follow-up and treatment, these 4 patients with permanent CH may have been exposed to a protracted period of hypothyroxinemia.

Preterm infants often have delayed maturation of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis [8]. By description, there is a lag in the normal postnatal TSH rise such that there is an initial period of low T4 with normal or low TSH, after which the physiologic neonatal TSH surge manifests. In a review of very premature infants (birth weight <1,499 g), Woo et al. noted a mean peak TSH=62 mU/L at 21 days of age with resolution of the TSH surge by 55 days [6]. Four of the preterm infants in our study (cases 4–6 and 8) developed strikingly high TSH values (TSH range, 190–957 mU/L) on either the second NBS and/or serum testing at between 12 and 79 days of age, consistent with a delayed TSH surge. A chart review of these cases confirmed that iodinated radiographic procedures had not been performed before this TSH surge (Table 1). Indeed, in the quadruplets (cases 5–8), urinary iodine levels were low to normal on day 30 of life. Most clinical evidence indicates that premature infants exposed to iodine are at much higher risk of hypothyroidism via an exaggerated Wolff-Chaikoff effect [18]. This may be due to increased absorption of iodine by the immature thyroid when exposed to iodine-enriched compounds such as radiographic contrast media. Even though all measured urinary iodine levels were normal in these babies, recent evidence supports that lasting thyroid dysfunction may still be present up to 1 year after iodine exposure [19].

Of note, 2 of the quadruplets (cases 6 and 7), who initially appeared to have a prematurity-related delayed TSH surge, were subsequently shown to have permanent primary CH. Their TSH values on or off levothyroxine ranged from 9 to 14 mU/L with normal free T4. This phenomenon was also observed by Cuestas et al. [20] concerning persistent neonatal hyperthyrotropinemia. Recently, McGrath et al. [9] also confirmed the importance of long-term follow-up of these preterm infants, noting 22% with permanent CH. One of the remaining 6 premature infants in our study (case 12) demonstrated persistently low T4/ TSH for 46 days of life before levothyroxine was started. This infant was not exposed to dopamine but had intermittent glucocorticoids, both of which suppress thyroid function.

Of the 2 infants diagnosed with CCH (cases 1 and 10), case 1 had an isolated TSH deficiency and a small Rathke cleft cyst, a malformation that has been associated with pediatric pituitary dysfunction [21]. Case 10 has not yet undergone pituitary imaging. Of importance, both cases with CCH in this study had initial serum free T4 in the moderately severe CH range of 4.38–10.0 pmol/L [1] and were not treated until 11 weeks of age, observations that emphasize the importance for early detection [11].

Central CH has an incidence in 1:20,000 using screening algorithms that measure T4 in concert with TBG and TSH. However, earlier reports suggest prevalence rates closer to 1:100,000 [22]. One study using T4/free T4 and TSH noted a CCH prevalence of 1:160,000, while another using T4 (<58.0 nmol/L) and TSH (<10 mU/L) noted central CH in 1:23,000. Not unexpectedly, detection rates will be diminished in NBS programs that are TSH-based [17]. Concerning this study, it should be mentioned that one additional case of CCH was excluded from our study cohort because full data on both the 1st and 2nd NBS were missing. If included, 3 cases of permanent CCH were detected by NBS per 472,000 infants screened, yielding a prevalence of CCH of 1:157,000. Clinical evidence supports, however, that most cases of CCH are diagnosed clinically rather than by NBS [10].

Three of the patients in this review were NBS-positive for low T4 and normal TSH on the 2nd NBS. Case 12 was an extremely premature infant with persistently low serum free T4 and TSH values (levothyroxine treatment on day 78) who was eventually shown to have transient CH. This patient was not treated with dopamine, but had intermittent glucocorticoids for lung disease. This clinical scenario is an ongoing challenge in the NICU, in which the complexity of care predisposes infants to euthyroid sick syndrome and exposure to agents such as dopamine and glucocorticoids, both of which can suppress pituitary-hypothalamic function [23]. Case 11 had a forme fruste prolonged period of low free T4 with normal TSH but eventually developed an elevated TSH=9 mU/L at 4 months of age consistent with primary hypothyroidism (Table 1). Why this otherwise healthy term infant did not mount an earlier TSH response to her progressive hypothyroidism is unclear, although subtle resolving hypothalamic/pituitary insufficiency is possible [24]. In addition, there was no history of maternal hypothyroidism, siblings with CH, or iodine exposure in this infant. The third case diagnosed by 2nd NBS was a term baby (case 10) with CCH (discussed previously).

Case 3 is instructive for having 3 conceivable reasons for neonatal thyroid dysfunction, namely, prematurity, maternal thyroid disease on treatment, and multiple hemangiomas. This baby was born at 1,500 g; hence, a delayed TSH surge was less likely compared to more premature infants (<1,499 g) [6]. Maternal autoimmune hypothyroidism can be associated with blocking antibodies that induce a transient primary CH. The delayed onset at 17 days of age and ultimate diagnosis of transient CH could plausibly be a result of these antibodies. Thyroid blocking antibodies were not measured. Several cases of transient CH caused by infantile hemangiomas containing thyroid deiodinase have also been described. Thyroid deiodinase inactivates T4 by converting it to reverse T3, which is an inert form of the hormone. Thus, the multiple hemangiomas seen in this case could have been a cause of this infant's transient CH [25,26]. While an exact cause for this infant’s transient CH was not determined, it demonstrates the potential pathophysiologic complexity of neonatal thyroid dysfunction.

In summary, lowT4/TSH was identified by NBS in a cohort of 12 infants, all of whom were referred for evaluation and treatment of CH. While all infants had normal thyroid glands by ultrasound, 4 had permanent CH after 3 years of follow-up. Concerning the recognized TSH surge of premature infants that is most often associated with transient CH, 2 of the 7 premature infants in this study with this delayed TSH surge had permanent CH. These results highlight the fundamental importance of following neonates with lowT4/TSH whose potential thyroid dysfunction ranges from transient hypothalamic/pituitary insufficiency to significant primary and central hypothyroidism requiring long-term treatment. This concern is heightened by reports [20] demonstrating that even transient neonatal thyroid dysfunction may have long-term adverse developmental repercussions.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Ethical statement

Institutional Review Board of University of Alabama at Birmingham (IRB-151104007) approval was obtained for this retrospective review of patient medical records with waiver of informed consent.