Evaluation of bone mineral status in prepuberal children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Many studies have reported that patients with type 1 diabetes have reduced bone mineral density (BMD). We assessed bone status in prepubertal children with type 1 diabetes mellitus (type 1 DM) at initial diagnosis and investigated factors associated with BMD.

Methods

Prepubertal children (n=29) with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes from 2006 to 2014 were included. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry measured regional and whole-body composition at initial diagnosis. BMD was compared with healthy controls matched for age, sex, and body mass index (BMI).

Results

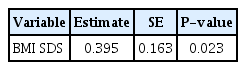

The mean age of all subjects (16 boys and 13 girls) was 7.58±1.36 years (range, 4.8–11.3 years). Initial mean glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level was 12.2%±1.9%. The mean BMD z-scores of lumbar spine, femur neck, and total body were not significantly different between patients and controls. Three patients (10.3%) had low bone density (total body BMD standard deviation score [SDS] < -2.0). To identify determinants of lumbar spine BMD z-score, multivariate regression analysis was performed with stepwise variable selection of age, pubertal status, BMI SDS, insulin like growth factor-1, and HbA1c. Only BMI SDS was significantly correlated with lumbar spine BMD z-score (β=0.395, P=0.023).

Conclusions

Prepubertal children with newly diagnosed type 1 DM had similar bone mass compared to healthy peers. However, patients with low BMI should be carefully monitored for bone density in type 1 DM.

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is an autoimmune disease caused by pancreatic beta cell destruction that usually presents in children and adolescents. Patients with T1DM are at risk for the development of serious complications, such as retinopathy, neuropathy and nephropathy during the disease course [1]. Complications associated with diabetes extend to other organ system including the skeletal system in adults [2]. T1DM is associated with a risk of decreased bone density, even in children and adolescents [3-6].

Diabetic complications, age at onset of diabetes, glycemic control and disease duration may affect bone mass in T1DM. However, there is no agreement on the influential clinical determinants of bone density [7]. Also, insulin is considered an anabolic agent for bone, so decreased insulin secretion before the onset of diabetic symptoms may affect bone status [8]. However, most of the previous studies evaluated bone density after diagnosis. There have been few reports on bone mass at initial diagnosis of T1DM in children and adolescents [6,9,10].

The purpose of this study was to evaluate bone mineral density (BMD) in prepubertal children with T1DM at time of initial diagnosis and to investigate the various factors associated with BMD.

Materials and methods

1. Study population

Of the 85 patients diagnosed as T1DM from August 2007 to June 2014 at Ajou University Hospital, we enrolled 29 prepubertal children who measured BMD. All patients needed to take either conventional or intensive insulin treatment, and none had microalbuminuria, retinopathy and neuropathy at the time of diagnosis. None had a fracture history. Patients with other chronic diseases and metabolic disorders were excluded. Patients who were taking medication to affect bone mineral metabolism, such as glucocorticoid, were excluded. The control group consisted of 92 healthy prepubertal children matched for age, sex, and body mass index (BMI) [11].

2. Study design

Patients' height, weight, and pubertal status were collected from the clinical charts and electronic medical records at the time of diagnosis. Height was measured using the Harpenden stadiometer (Holtain, Crosswell, Crymych, UK) and weight was recorded with a digital scale. BMI was calculated as weight divided by height in (kg/m2). Pubertal stage was determined as previously described [12]. The prepubertal stage was defined as a lack of breast development in girls and a testicular volume<3 mL in boys. Only prepubertal children were included because sex hormones can affect bone density. The standard deviation score (SDS) for height, weight and BMI were calculated according to the 2007 Korean National Growth Charts [13].

Blood samples were obtained for the determination of serum values of calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and insulin like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). Serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, and ALP was measured using a TBA200-FR automatic analyzer (Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan). Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level was measured with the use of the COBAS Integra 800 turbidimetric inhibition immunoassay (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Serum IGF-1 levels were measured using the NEXT IRMA CT BC 1110 immunoradiometric assay (Biocode Hycel, Pouilly En Auxois, France). IGF-1 SDS for age and sex was calculated according to Korean IGF-1 levels for the same age and sex in healthy children and adolescents [14].

BMD was measured in all patients by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry within one week after initial diagnosis. Dualenergy X-ray absorptiometry was performed to measure regional and whole-body composition with the Lunar Prodigy device (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI, USA). BMD (g/cm2) at the level of the lumbar spine L1–L4 (LS), femur neck (FN) and total body (TB) were measured by whole-body scan. Subjects were carefully repositioned at every scan to minimize errors associated with changes in measurement geometry by single experienced operator. The coefficients of variation for BMD were 0.339% (L1–L4), 0.679% (FN), and 0.454% (TB). Z-scores of BMD at each site were calculated using data of healthy Korean children and adolescents (262 girls and 252 boys) after adjusting for height-for-age [11,15]. Low bone density was defined as BMD z-scores < -2; the low range of normality, between -1 and -2; normal BMD was defined as z-scores ≥ -1 [16]. The study design was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ajou University Hospital (AJIRB-MED-MDB-17-117). Written informed consent by the patients was waived due to a retrospective nature of our study.

3. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 21.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). An independent t-test was used to assess the difference in the mean BMD z-scores at lumbar spine, FN and TB between patients and controls. Pearson correlation was examined to determine the relationship between BMD z-scores at each site and other clinical variables. Finding significant association with BMD z-scores at each site, linear regression was performed for multivariate analysis with stepwise variable selection, including age at diagnosis, sex, BMI SDS, HbA1c, and IGF-1 levels. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05. Results are described as mean±standard deviation unless otherwise stated.

Results

Clinical characteristics of all patients were shown in Table 1. The mean age of patients was 7.58±1.36 years (range, 4.8–11.3 years). Seventeen patients (58.6%) were treated with intensive insulin therapy and 12 (41.2%) were treated with conventional insulin therapy. The mean insulin requirements of all patients were 0.85±0.25 unit/kg/day. The initial mean values of pH and bicarbonate (mEq/L) were 7.35±0.1 and 18.0±6.2, respectively. Nine patients (31.0%) were diagnosed with diabetes ketoacidosis at initial admission. Calcium, phosphorus and ALP levels were within normal limits (data not shown).

Mean BMD z-scores of LS, FN, and TB were not significantly different between patients and controls (Table 2). Low bone density (z-scores < -2) was found in 3 patients (10.3%) at the LS, 4 patients (13.7%) at the FN, and 3 patients (10.3%) at the TB. Low range of normality (z-scores between -1.0 and -2.0) at LS, FN, and TB were found in 31.0%, 10.3%, and 20.6% of the patients, respectively. When the mean BMD z-scores were analyzed depending on sex, there were no significant differences between males and females with T1DM (Table 2). There were no significantly differences between patients with or without diabetic ketoacidosis in the mean BMD z-scores (data not shown).

Bone mineral density z-scores of lumbar spine, femur neck, and total body between patients and controls and in patients divided by sex

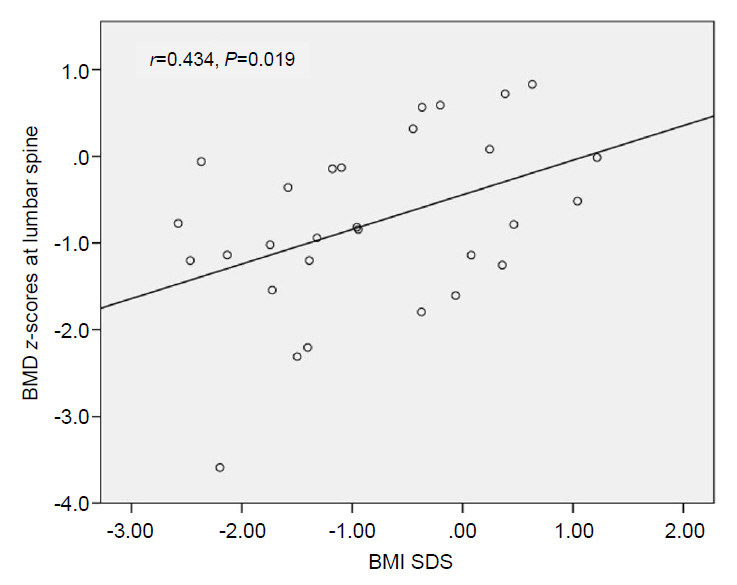

Pearson correlation analysis was performed to investigate the correlation between several variables (age at diagnosis, HbA1c, IGF-1 SDS, and BMI SDS) and BMD z-scores. Only BMI SDS was significantly and positively associated with BMD z-scores at LS (Fig. 1).

Correlation between bone mineral density (BMD) at lumbar spine and body mass index standard deviation score (BMI SDS) in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus.

In a stepwise multivariate regression analysis including age at diagnosis, sex, BMI SDS, HbA1c, and IGF-1 SDS levels as independent variables, and tested in a model with BMD z-scores at LS as dependent variable, BMI SDS was identified as significant independent predictors for BMD z-scores (Table 3). Age at diagnosis, sex, pubertal status, HbA1c and IGF-1 SDS levels were not significantly related to BMD z-scores at LS

Discussion

Prepubertal children with T1DM did not display significantly lower BMD compared to normal healthy peers at initial diagnosis. BMI SDS was positively correlated with BMD z-scores at LS.

Low bone density (z-scores < -2.0) and low range of normality (z-scores between -1.0 and -2.0) at LS were found in 10.3% and 31.0% of the T1DM patients, respectively. Onder et al. [17] reported that 35% of 100 pediatric patients with T1DM showed abnormality of LS BMD (z-scores < -1.0), similar to our study. In other studies about children and adolescents, the proportion of z-scores < -1 at LS ranged from 26.7% to 45.4% [9,10,18,19]. In prior studies, most children and adolescents with T1DM displayed significantly lower BMD at one or multiple skeletal sites, although a few studies detected no difference in BMD z-scores between T1DM patients and healthy controls [7,20]. Most previous studies evaluated bone density after diagnosis and disease had progressed. A few studies addressed BMD in T1DM at initial diagnosis or early in the disease course. The strength of our study was the measurement of bone density at time of diagnosis in prepubertal children. Presently, LS BMD z-scores at initial diagnosis were -0.76±1.00 and scores were lower than zero. However, no significant difference between patients and healthy controls was evident. Gunczler et al. [10] studied BMD at a mean of 5.8±1.5 months after diagnosis in 23 prepubertal children with T1DM. LS BMD z-scores were decreased compared to normal controls. Camurdan et al. [9] reported that LS BMD z-scores of 16 patients with newly diagnosed T1DM were lower than zero (-0.49±0.97), but were statistically insignificant. In adults, LS BMD z-scores of 32 adult-onset T1DM patients at the time of diagnosis were -0.61±1.23 and were significantly lower than a matched normal population in [21].

The underlying mechanisms of reduced bone density in T1DM are not fully known and no single mechanism can explain the effect of T1DM on BMD [22]. Insulin deficiency and hyperglycemia are well known characteristics of T1DM. Low insulin levels may be crucial for low bone density [23,24]. Insulin replacement in rats with diabetes has been shown to normalize bone turnover [25]. Hyperglycemia also suppresses osteoblastic differentiation and signaling, potentially resulting in decreased bone formation [26]. So, we hypothesized that patients with newly diagnosed T1DM would have lower BMD compared to their healthy peers. However, our results showed that BMD z-scores were not reduced at the early course of the disease. Also, insulin and hyperglycemia were not only the crucial role of decreased bone density in T1DM. Other factors, such as IGF-1 level, incretin and inflammation, can affect bone formation and resorption [27]. Especially, bone health could be more vulnerable in those who develop T1DM earlier in their lives because childhood and adolescence are critical periods for skeletal development [28].

There have been variable factors that are associated with decreased bone mineralization in type 1 DM. In present study, low BMI was significantly correlated with low BMD. Low BMI is associated with low BMD [29]. Neumann et al. [30] reported that low BMI is a predictor of low BMD in women with T1DM. In another study, LS and FN BMD were independently correlated with BMI in adults with T1DM [31]. These studies suggest that body composition and lean body mass may affect the bone density in people T1DM. In addition to BMI, IGF-1 levels, bone size, disease duration, glycemic control, age and sex have been associated with reduced bone density [4,30-34]. But the clinical determinants of bone health in T1DM remain debatable.

The current study had several limitations. First, the cross-sectional analysis did not allow the assessment of causality. Second, we did not evaluate bone resorption and formation markers, such as osteocalcin. Third, we did not investigate vitamin D, PTH, hypercalciuria, and physical activity, which are known to be associated with bone health. Fourth, the sample size was relatively small. Finally, the duration of hyperglycemia and insulin deficiency of patients with T1DM may be short enough to affect bone health. Therefore, a long-term study involving a larger cohort is required to investigate the pathogenesis of low BMD and related factors in children and adolescents with T1DM.

In conclusion, prepubertal children with T1DM had similar bone density compared to healthy controls at time of initial diagnosis. Low BMI was the only predictor of decreased BMD. Based on our results, type 1 DM patients with low BMI should be carefully monitored about bone density, although the screening of bone status at initial diagnosis in all children with T1DM may not be necessary.

Notes

Conflict of interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.